Sunscreen: Making Its Way Through the Ocean

By Safina Center Intern Lindsey Neuwirth

Photo via flickr Kelsey Roberts, USGS

The ripe coconut scent hits my nose as I douse the greasy substance across every inch of exposed skin. The smell never fails to bring me back to my childhood, as I used to gear up for long days at the beach, splashing in the waves and digging through the sand. Sunscreen is essential for our safety, providing protection from harsh sunburns and preventing potential skin damage. However, this protection comes at a cost, as the chemicals and components of sunscreen have damaged and debilitated ocean corals and plant life for many years, only recently revealing its true detriment to the environment.

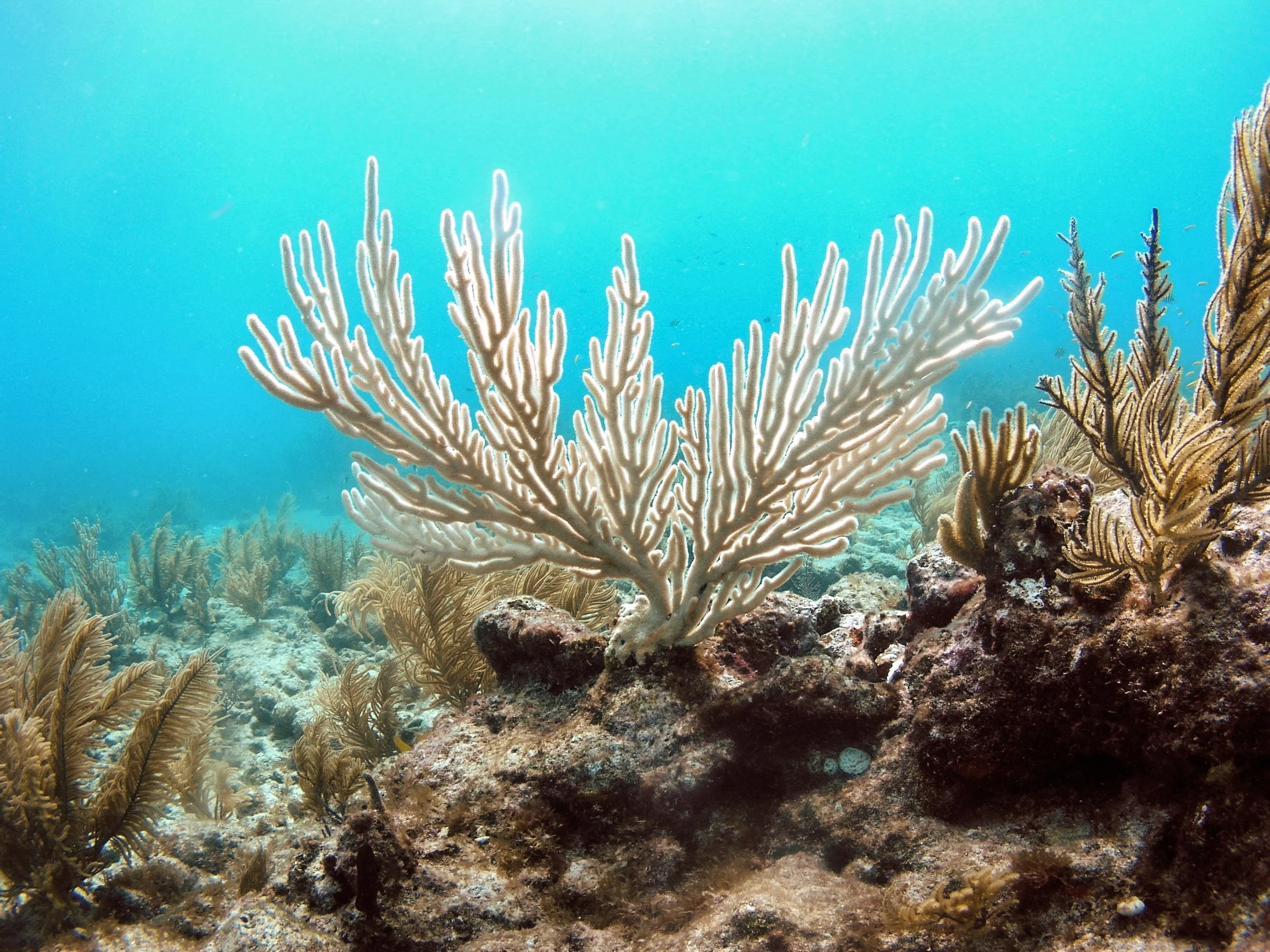

To provide effective protection, many sunscreens contain chemicals that absorb or block the sun’s rays, commonly known as ultraviolet filters, useful for us, but toxic to ocean ecosystems. When this sunscreen is applied prior to going in the water, approximately 25% of the product washes off. And since sunscreen is heavily and consistently used by beachgoers, this remanence is a major problem for the marine environment. Coral reefs, diverse ecosystems that form the foundation of ocean function, are particularly susceptible to these chemicals. When exposed, these UV filters can induce viral infections in coral, promoting coral stress, which causes them to expel their crucially important algae and eventually starve, a process known as bleaching.

But corals aren’t the only marine organisms at risk. In various species, including the Fathead minnow fish, the Japanese medaka fish, snails, and copepods, reproduction was negatively affected by exposure to sunscreen. In clownfish, ultraviolet filter exposure resulted in disrupted swimming behavior and even mortality in some cases. Death was also highly prevalent in clams and Senegalese sole fish.

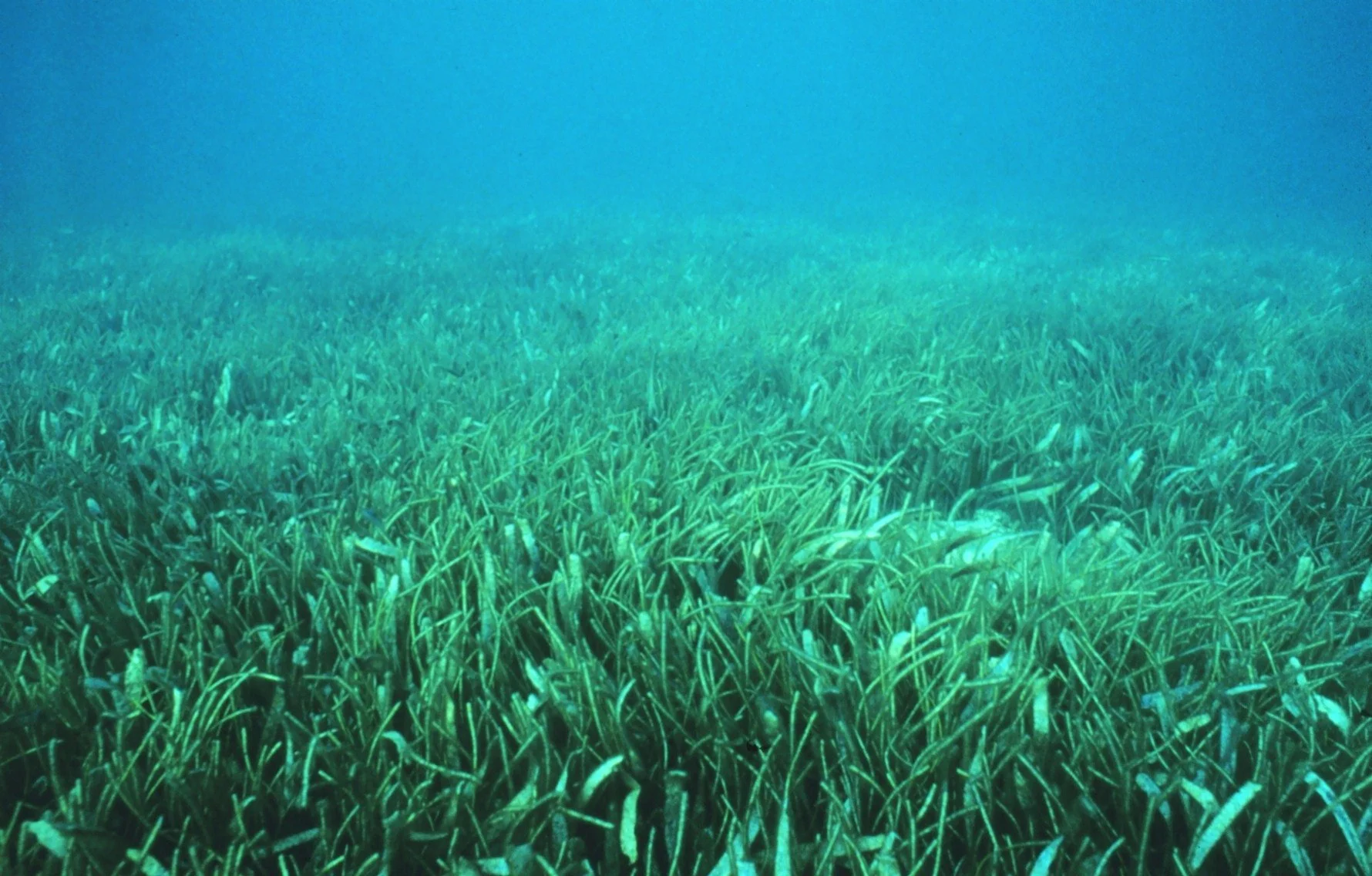

A seagrass meadow Photo via Flickr Heather Dine

New research in the Mediterranean recently found components of ultraviolet filters in the roots of Posidonia oceanica, a species of seagrass, that forms large seagrass meadows. Seagrass is essential. Collectively, it absorbs approximately 10 percent of all carbon that is absorbed into the ocean. Seagrass also serves as a nursery for many species of marine organisms, providing food and shelter. Since the Mediterranean is a prime tourist destination, the marine environment is frequently exposed to sunscreen products, leading to higher levels of UV filter exposure.

However, the study did not examine how the accumulating ultraviolet filters in the seagrass actually affected the health of the plant. As an essential organism for ocean ecosystems and for carbon sequestration, further research into how seagrass is affected by ultraviolet filters is crucial to fully understanding the implications of sunscreen on the ocean. Given the harmful effects ultraviolet filters have on other marine organisms, it is highly likely that seagrass will also be at risk.

Coinciding with further research on the negative impacts of sunscreens on the marine world, several nations, many of which are tourist dependent, have enforced bans on the use of sunscreens that are degrading to the environment. In the U.S. Virgin Islands, the sale, use, and possession of sunscreen products containing the most known harmful ultraviolet filters called oxybenzone, octocrylene and octinoxate are prohibited. Similarly, Hawaii, Key West in Florida, Aruba, Bonaire, Palau, and specific reserves in Mexico have also placed bans on such products.

Further evidence can be provided by continuing to examine the negative effects of ultraviolet filters to establish policies to protect the marine environment from harmful contaminants in sunscreens. With more research regarding what chemicals are degrading to the environment, products that are effective at providing sun protection and are safe for aquatic organisms can be developed and used widely.