A Treaty to Protect the High Seas–Before Time Runs Out

By Safina Center Intern Lindsey Neuwirth

Vessel on the High Seas: Photo via Flickr Lars Plougmann

Your body tenses as the cool salty water rushes over your toes and creeps up your ankles. You look down at the wet sand as the wave retreats and see sand crabs quickly burrowing down before the next rush of water comes. You look up just past the breaking waves and see a glimmer of light, as the sun reflects off a dolphin’s silver body gliding in and out of the water. As the midday sun is slowly beginning to set, making its way across the sky, you stare out into the horizon. Creating a clean line where the sky meets the sea, it creates the illusion of the end of the earth. It goes on for miles, stretching far beyond your vision. You can’t help but wonder what life is like out there.

This vast place, only reachable by large vessels, is called the high seas. The high seas are areas of the ocean that are beyond a nation’s jurisdiction. Covering two thirds of the world’s oceans, they are home to immense biodiversity, essential to the function of ocean ecosystems. The high seas provide important migratory routes for key species such as whales, seabirds, turtles, tunas and sharks. They also support many large fisheries and are home to several deep-water corals and undiscovered marine life that potentially hold life-changing medical resources. Unfortunately, the high seas lack governmental regulation as they do not ‘belong’ to a single nation. Figuring out how to govern this wild place has been an ongoing challenge for several years.

Since 2018, the Intergovernmental Conference, a group made up of representatives from different member governments in the United Nations, has been holding sessions to discuss the formation of an international legally binding treaty to regulate the high seas.

After three fruitless meetings, the General Assembly, otherwise known as the main policy makers of the United Nations, finally approved the creation of a draft treaty. However, due to the Covid-19 pandemic, the fourth session to present the treaty was postponed up until this past March.

However, when the postponed United Nations conference ended on March 18th , there was no approved draft nor finalized treaty. This lack of decision was fueled by a multitude of issues. First, the equitable management of valuable or potentially valuable resources from marine organisms and plants found in the high seas posed a major challenge, as technically the high seas belong to everyone equally, but many developing nations do not have the means to access these resources. Another disagreement among delegates was the assertion that fishery management and policy should not be included in the treaty, despite the large fish stock that the high seas provide. With no consensus on this issue, it became difficult to discuss how a framework for establishing Marine Protected Areas would be put in place without considering the management of any fishery. The good news is that due to the importance of such an agreement, another meeting will be held this coming August to review new revisions addressing these concerns and to hopefully make a final negotiation.

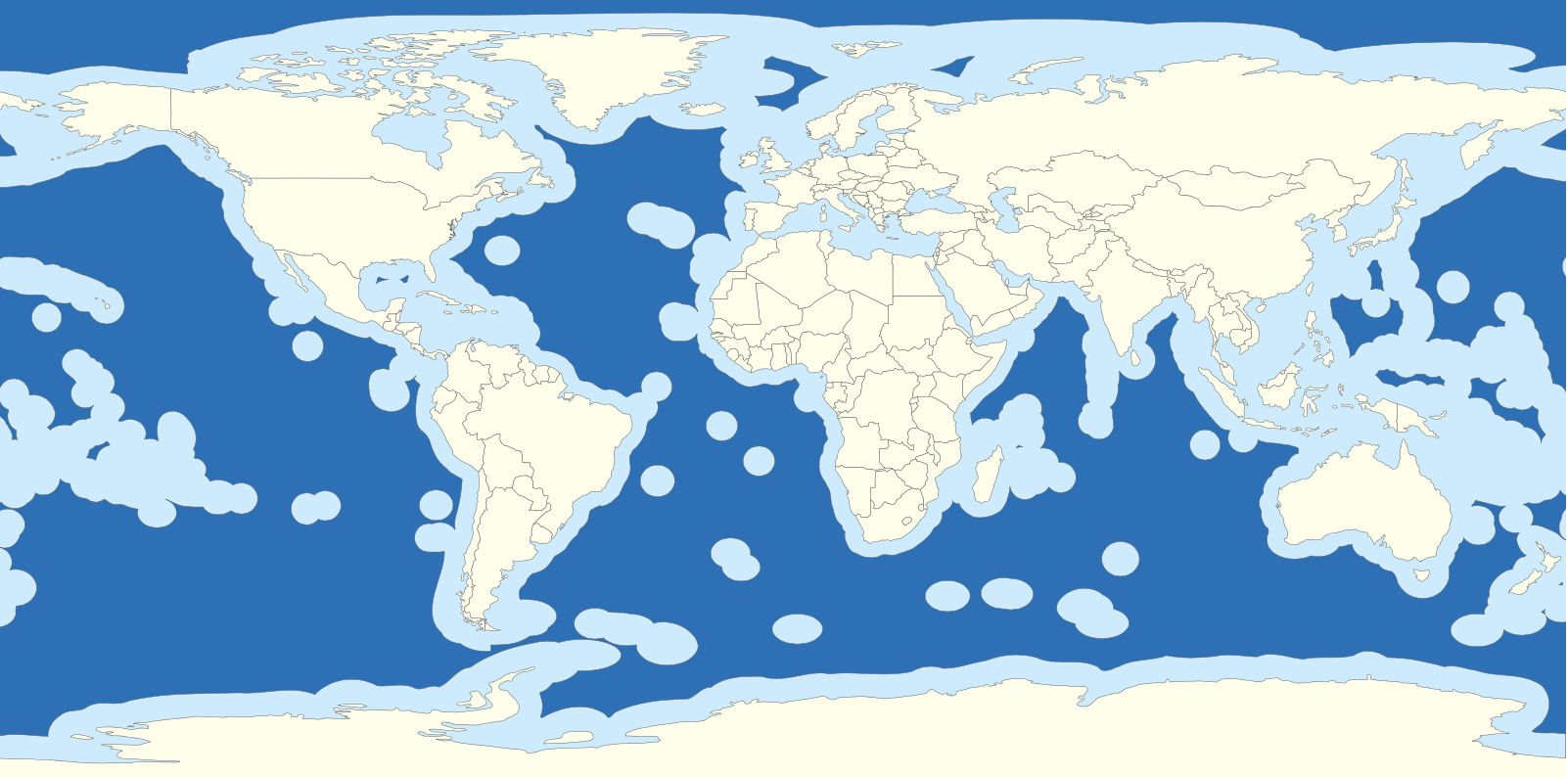

Map of international waters Photo via Wikimedia Commons

An effective treaty is crucial when considering how to monitor the high seas. A future treaty must address the gaps in current regulation by establishing ecosystem based overarching governance principles, creating a framework for establishing Marine Protected Areas, and drafting policy for marine genetic resources, technology transfer, and fisheries. If the UN can address these gaps, an official treaty can be settled.

The United Nations Global Biodiversity Framework set a goal to protect 30 percent of the ocean by 2030. With this deadline only eight years away, we need an official agreement to protect the high seas. The high seas make up 64 percent of the total ocean area, with the rest dedicated to a nation’s economic exclusive zones, the 200 miles off a nation’s coast where they have complete legal jurisdiction. Since it may be difficult for individual countries to protect these zones, that makes the protection of the high seas even more important towards reaching the United Nations goal of protecting 30 percent of the ocean. The UN must make urgent adjustments to the draft treaty before the next session this coming August if they hope to make real change for the High Seas and those who depend on its resources.

Life out on the high seas is crucial to the proper function of our environment. What affects the high seas, affects our coastlines, which then affects us. A treaty for sustainable and equitable management can ensure that all nations value the benefits of the high seas in a way that puts our planet first. Next time as you gaze into the horizon, remember that the illusive perfect line created as the sky meets the sea holds a great wealth of life that needs protection.