Zafimaniry Woodworking: a Lasting Tradition?

By Safina Center Fellow Alain Rasolo

A Chameleon made by a Zafimaniry woodcarver. ©Alain Rasolo

About the Woodworks

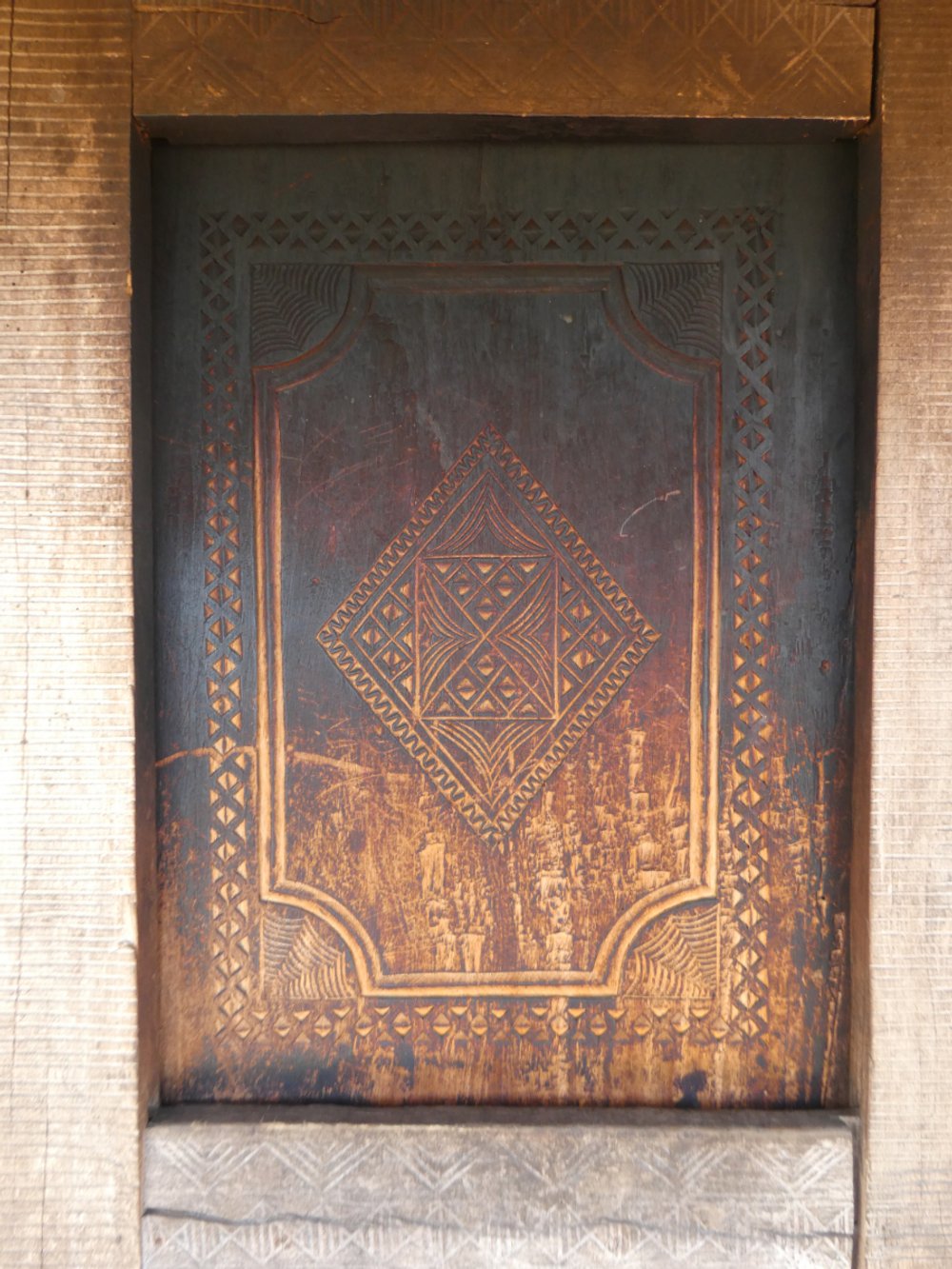

The Zafimaniry community lives in the southern part of the highlands of Madagascar. They carry on a tradition of skillful carpentry and meaningful woodcarvings that are recognized by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization as Masterpieces of Oral and Intangible Heritage of Humanity. Their wooden houses and granaries are built with mortise and tenon joints without the use of nails or screws. Nevertheless, these houses have withstood years of passing cyclones and, to René Guy—one of the most accomplished Zafimaniry woodcarvers—and his family, are even preferred shelters to more recent brick and mud houses. The walls, windows and doors of such homes are ornamented with intricate carvings, each carrying various meanings. To name a few, the sun rays represent a shared prosperity; the spider web represents family ties; the honeycombs (off of which the ancestors used to live, from the nearby forest) evoke community life; the outer ropes tie everything together to show solidarity; and the scissors refer to the practice of circumcision and the transition to manhood.

On the issue of lasting

One can make the case that the Zafimaniry heritage is affected by its own fame. Decades of high-volume production to supply the artisan market in the nearest city of Ambositra and large sales to tourists have led to an unsustainable exploitation of the surrounding forests. Additionally, Tavy, or slash-and-burn agriculture, has accelerated the forest’s dwindling. Ironically, in the past, the absence of nails in the building of the traditional wooden houses made it efficient to dismantle them when it was time to move on to other forested areas, as the soil would inevitably lose its nutrients because of the Tavy technique. Together, these issues have put a strain on the woodcarvers of Antoetra and their surroundings.

So, what is the future of this art form then? René Guy, who owns a workshop in Antoetra, is not very optimistic. Competition for business from tourists can turn bitter at times, he says, which affects his relationship with his peers. And even with all his success, he can only be a part-time woodcarver, as he cannot always rely on his revenues to support him and his family. He spends most of his time growing rice and taking care of his fish pond.

Hope

However, the future is not all doom and gloom. René Guy is interested in continuing his passion despite the hardship. He can still rely on people living near the rainforest (about 20 km away) to supply the larger planks of wood needed to make doors and windows. The making of planks from invasive eucalyptus and pine trees to build the houses relieves the pressure on the use of endemic rainforest trees. He also collects and uses old tree roots that have been left behind during the Tavy clearings to make smaller items. And, although René Guy hasn’t particularly encouraged his son to continue on his craft, he says the lad has an innate interest in the carvings and has even explored expanding his own portfolio to include new utensils.

In recent years, there has also been an effort by the local authorities, with support from foreign sponsors, to promote the making of new houses in the traditional style by René Guy and the four other woodcarvers in the village. This initiative aims to refocus the carpentry practice around the idea that the making of carvings is, in itself, an enjoyable and meaningful activity, as well as a long-held tradition that should be continued. Being able to sell to tourists, the local authorities say, is just an added benefit of continuing the tradition.

The forest of Bekaraka is nearby

The surrounding landscape of the village is very typical to the highlands: rice paddies, vegetables, corn and cassava fields, dry grassland, and eucalyptus and pine tree woods. But about two and a half kilometers north of it lies the lush forest of Bekaraka. It’s a small (about 150 hectares) remnant of what was the more inland part of Madagascar’s eastern rainforest. After an hour of walking, we were welcomed by the humid forest. The ground was often covered by mosses and there were bamboos, screwpine, ferns, palms and all sorts of trees, adorned with many orchids, most of which could be identified by Fidi, my accompanying woodcarver (Jumellea sp, Aeranthes caudata, etc). We also heard the whistling of a Vasa Parrot (Coracopsis vasa) and the “brr-dd-t” like call of a blue coua (Coua caerulea). The forest is managed and protected by the VOI of Antoetra, the local community organization. The ban on cutting down trees here is well enforced, said René Guy, but harvesting fast-growing bamboo is tolerated, as it is used to build baskets and the roofs of traditional houses. There is also currently an effort to reforest the surroundings of the Bekaraka forest.