Wonders Under Threat

By Safina Center Fellow Belén Garcia Ovide

Blue whale preparing for a dive ©Nico Schmid

Clear evidence shows that we are reaching the inevitable limits of the resilience of most of our oceans and seas. Despite increasing international policies to address climate change issues and to regulate human-made impacts, the reality is that we have already reached crucial tipping points on the state of the Earth, leading to irreversible change.

In the Arctic regions, changes such as sea ice loss, glacial melt, and ecosystem shifts are not only threatening wildlife, but also having direct social impacts on the cultural identities, health, food sovereignty, and water security of small communities.

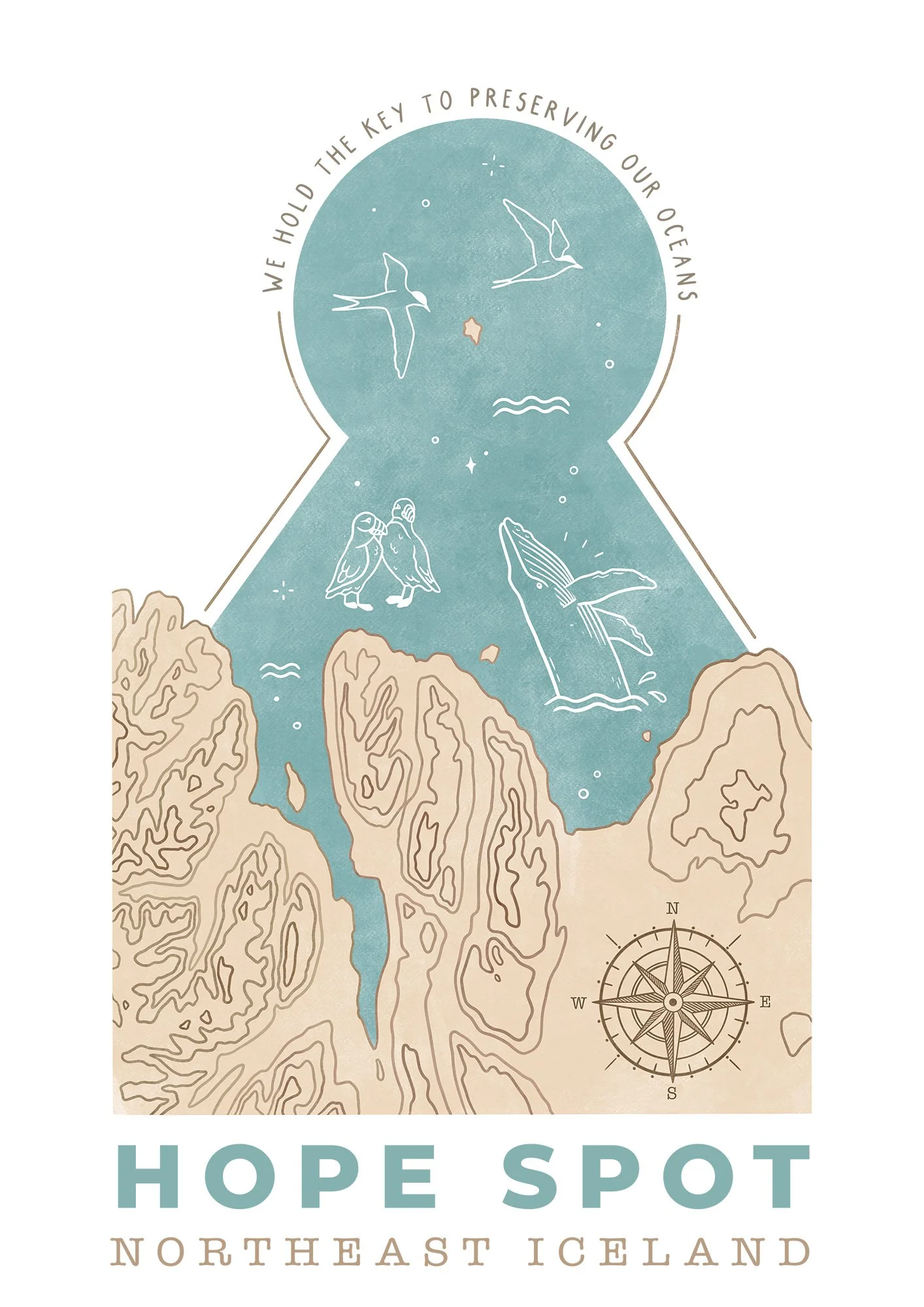

The Northeast of Iceland was recently recognized as the first Hope Spot in its country in June 2023. The strategically designated area includes three biologically critical regions: Skjálfandi Bay (SK), a southern sub-arctic deep-water bay by Húsavík town; Eyjafjördur (EY), which is the longest fjord in Iceland and spans 40 miles from its mouth to Akureyri town; and Grímsey (GR), situated at the most northern tip of Iceland’s waters at 66 degrees north. This area has traditionally marked the boundary waters for crossing into the Arctic Circle between the North Atlantic Ocean and the Greenland Sea. Here, seasonal upwelling events and the influence of powerful rivers and glacier activity trigger nutrient-rich waters and allows marine biodiversity to proliferate in a dynamic environment.

Designed and illustrated by Styngvi

The Hope Spot provides habitats for both resident and migratory species and serves as important feeding and breeding grounds to a myriad of bird and marine mammal species. It hosts up to 23 species of cetaceans—both resident and migratory species—including the endangered blue whales (Balaenoptera musculus) and hybrids between fin whales and blue whales. Seven pinniped species and 20 cetacean species have been reported. Coastal habitats on Lundey, Flatey, Grímsey, and Hrísey Islands, as well as Mánárey Islands (Háey and Lágey), and cliffs along the mainland (Tjörneslágin and Voladalstorfa) provide shelter and food sources for nearly 40 nesting bird species (of which 16 are seabirds), including some of the largest populations of sea birds in Europe such as the endangered Atlantic puffin (Fratercula arctica) and Arctic terns (Sterna paradisaea) (Birdlife, 2022). These places host diverse sea-bottom life—126 fish species and at least 47 species of invertebrates (Icelandic Institute of Natural History, 2001)—which are important for fisheries but also serves as feeding grounds for larger aquatic and coastal inhabitants.

In addition, the adjacent coastal communities of Húsavík and Akureyri are known for scientific research and a vibrant tourist economy, where whale watching has become one of the main attractions, especially in Skálfandi Bay—the whale capital of Iceland.

In these productive waters, life still thrives. However, these fragile ecosystems are currently under increasing threats and our aim at Ocean Missions is to bring awareness among the Icelandic population and to inform policy makers about the importance of implementing protection plans before it is too late.

In recent years, the implementation of industrial projects for the extraction of marine resources has become very popular in Iceland, yet not successful. The lack of a strong ocean law and the vague or non-existing regulations is attracting other countries to expand their business in Icelandic seas, where they can easily get permits. This is a massive threat the coastal ecosystems, and projects are already over-exploiting some of the most valuable Icelandic marine resources.

For example, the Icelandic Salmon fishing company is 50 percent owned by the largest Norwegian salmon companies. The expansion of their salmon farming and industry has created serious difficulties for local ecosystems, such as regular fish escapes and lice infestations putting the survival of the wild Icelandic salmon population at risk (Fishfarmingexpert, 2023).

Kelp forest ecosystems provide important habitats for a diverse assemblage of invertebrates, fish, and marine top-predators such as seabirds and sea mammals. Further, they serve an important ecological role by supporting the production of oxygen and carbon sink. Their protection is key to achieve the protection of strategically designated marine areas (Dexter K, 2019). Despite its critical importance for the health of our oceans and climate, kelp forests in the Artic have recently been the target for industrial exploitation and economic investment. In 2022, a permit was given to Íslandsþari ehf (Icelandic- Scottish company), by the government to build an industrial seaweed factory in Húsavík, a project worth three billion ISK, where a factory vessel will be in charge of removing (not just cutting) large quantities of kelp from the sea bottom near Skjálfandi Bay, with unknown consequences for the local biodiversity and ecosystem productivity (Hafstað. V, 2021). From the beginning of the project, it was clear that exports were sent to Europe and Asia and not being commercialized in Iceland, bringing little to no income to the country. Further, they argue that this project can create 80-90 jobs positions for the locals but the current unemployment rate in Húsavik is below 2.5% (BDEEX, 2022).

male Atlantic Wolffish guarding his eggs in a kelp forest. ©Strýtan DiveCenter

In 2023, residents in Húsavík teamed up and expressed their opposition to the regional government before the project began construction of its infrastructure. Interestingly, most of the arguments against the factory addressed the proposed location at the harbour, possible bad smells, and visual impacts for the residents, but very few arguments addressed the potential environmental effects to the kelp forests and fish communities. As for now, there are no signs of the project evolving here or elsewhere. Despite the apparent success of this case, this situation shows little awareness and sense of self-responsibility among the general population about the value of the ocean and the threats to it.

Looking at the big picture, limitations or restrictions on human activities in Icelandic shores and marine areas are almost non-existent in the country and only 1% of the coastal area is fully protected from human impacts (Mpatlas.org). Currently, none of these protected areas fall within the Hope Spot boundaries.

Iceland has not yet defined specific biodiversity objectives in its national Arctic policy and is behind schedule on delivering the goals proposed by the United Nations to protect at least 30% of the oceans by 2030 and in achieving the 12 UN sustainable development goals set in 2015, particularly regarding number 14, “life below water” (United Nations, 2015). In early 2022, the Hope Spot area was identified as within the targeted area for conservation proposed by WWF ArcNet, an Arctic Ocean network of priority areas for conservation (ArcNet, 2021).

On 2nd May 2024, we’re hosting an important event together with SVIVS (https://skjalfandi.org/), for the local community where the residents, local stakeholders and the municipality of Húsavík will gather to discuss about the future of Skjálfandi Bay. As part of the event and with the support of the national government, we will present an official proposal to start a pilot project for the implementation of the first Marine Protected Area in these waters’ region.

From Iceland, we at Ocean Missions, want to create a wave of action that will ignite people to protect the oceans worldwide, not only for the value of our marine resources, but because of the crucial role of the oceans for life on Earth.

Sunset in Skjálfandi Bay, Húsavík, Iceland ©Belén Garcia Ovide