The Opportunity in the Ross Sea

By John Weller, Safina Center Fellow

Adelie Penguins Hunting in a Crack in the Sea Ice. Photo: John Weller

The clock is ticking on one of our greatest environmental achievements. It is set to expire on December 1st, 2052.

On October 28th of last year, in a stone fortress in the center of Hobart, Tasmania, two dozen nations and the EU unanimously adopted the world’s largest marine protected area in the Ross Sea, Antarctica. I had devoted twelve years of my life to the fight for the Ross Sea, working in concert with and alongside hundreds of scientists and diplomats, dozens of conservation organizations and supporters, and multiple national governments to get to this moment. And I wish that you – you reading this – could have been there with us, on the floor of CCAMLR, the Commission for the Conservation of Antarctic Marine Living Resources, when it happened. The room packed with stoic international diplomats erupted. People were laughing and cheering and crying. Nations were literally hugging other nations.

NGOs Celebrating at CCAMLR 2016. Photo: John Weller

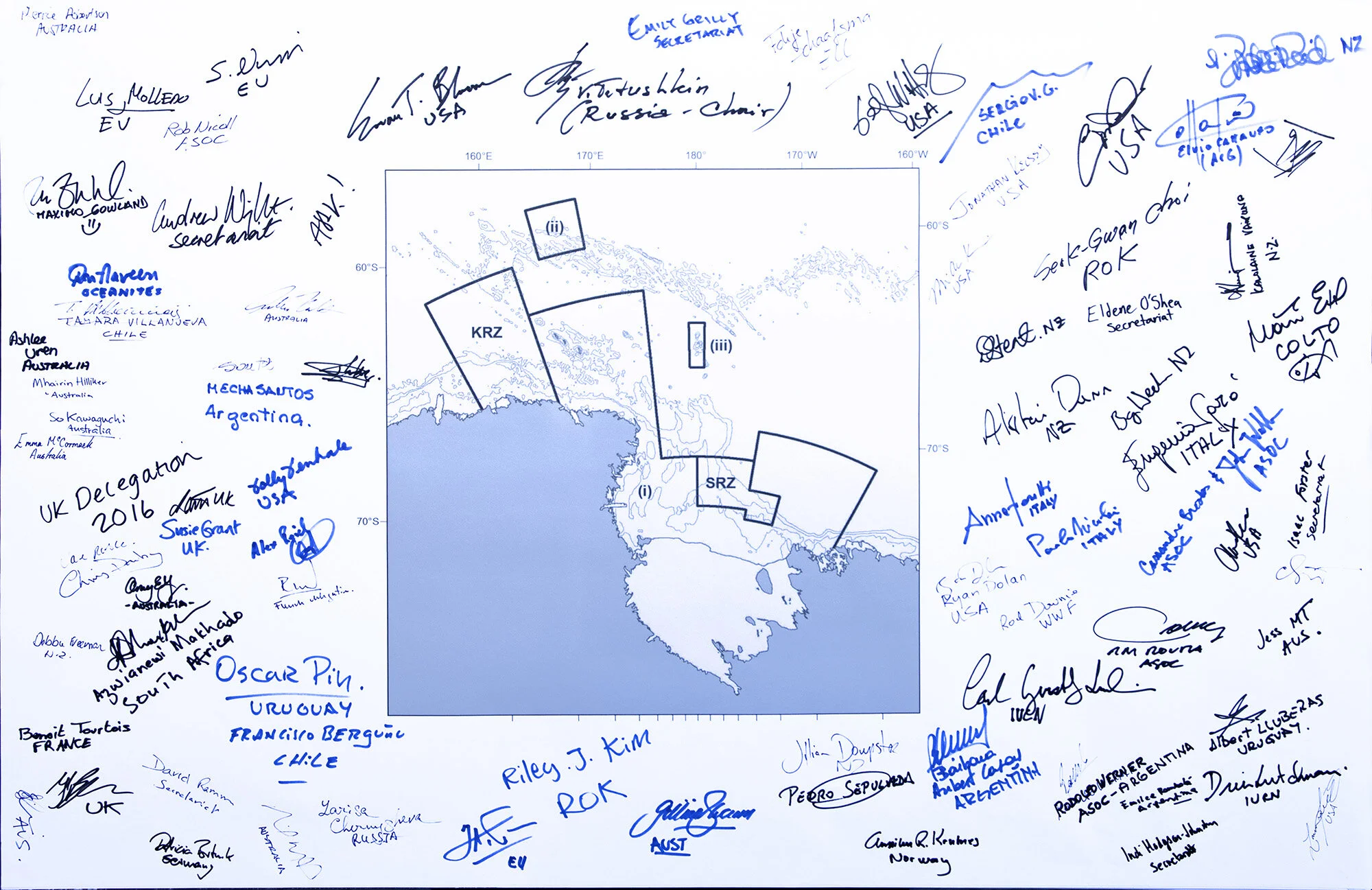

It was a stunning achievement. It is the first large-scale international marine protected area. It is a peace treaty. But what the MPA actually achieves needs further explanation. The original MPA, proposed by the US and New Zealand in 2012, was reduced in size by 40% through negotiations. The reduction was largely in the northern regions of the proposed MPA, which were designed to protect deep ocean ridges, thought to be the spawning grounds of the Antarctic toothfish, the largest predatory fish in the Southern Ocean and the target of a highly controversial multi-national fishery in the Ross Sea. A closer look at the boundaries of MPA reveals that it was designed to largely not interfere with the fishery, even as originally proposed. From the start, the Iselin Bank – a protrusion of the Ross Sea continental shelf, identified as the most biologically important area in the entire region, yet also where the bulk of the fishing is done – was left out of the proposal. Among other concessions, a Special Research Zone (SRZ) – where fishing will occur, though with a lower catch and a higher intensity of fisheries research to better monitor the fishery – was carved out of the remaining prime toothfish habitat along the Ross Sea continental slope. A Krill Research Zone (KRZ) was added to accommodate potential krill fishing interests. Finally, a sunset clause was added. The MPA is in force for 35 years, starting today. It will require a unanimous decision to readopt it in 2052.

Ross Sea MPA Boundary 2012 – 2016. Courtesy: John Weller

New Ross Sea MPA and Fishery. Courtesy: John Weller

In 2004, I read a scientific paper by Antarctic ecologist David Ainley in which he describes the Ross Sea as the last large intact marine ecosystem on Earth, and identifies the toothfish fishery as the most immediate threat to its integrity. The very idea that there could be just one truly pristine place left in the entire ocean, and that it too was facing the same fate of depletion, completely upended my world-view. It kept me up at night; it got deep under my skin; it became my all-consuming obsession, and I mortgaged my entire life to chase the beautiful vision of protecting the last pristine place. My vision was, perhaps, naïve, rooted in a romantic concept of “wilderness” as a place completely devoid of people, a concept that has almost no basis in our current reality. But in any case, that vision is in the past. The fishery in the Ross Sea, even if it turns out to be sustainable, will reduce the population of toothfish by 50%, intrinsically changing the food web. It likely already has. The opportunity to save the Ross Sea fully intact is gone. In that, we have failed. Now we must embrace the opportunity we have starting today, which is actually more important.

The Ross Sea MPA ecosystem will change, but if we can manage the fishery in a way that maintains the overall stability of the ecosystem, we will have accomplished something profound. CCAMLR has the chance to show the rest of the world, and particularly other Regional Fisheries Management Organizations (RFMOs), international governing bodies like CCAMLR, how to create a truly sustainable fishery in concert with strong conservation, embodying the ideal of ecosystem-based long-term precautionary management. Globally, more than 90% of fisheries were fully-exploited, overexploited or collapsed as of 2008. As top researchers have pointed out over and over, we are quite simply running out of fish, and the RFMOs that manage the catches of our last great fish stocks are failing. Tunas, for example, are managed by 5 RFMOs with jurisdictions around the world. These organizations have presided over the decline of nearly every tuna stock under their charge. Many of those stocks have plummeted. Only stocks of skipjack tuna, which is being caught and canned at a rate of 3,000,000 tons per year globally, have remained relatively stable. Leading fisheries researcher Boris Worm pointed out to me that skipjack tuna is perhaps the last great fish stock in the open ocean, and global declines in other fisheries have led to increasing pressure. Between 1994 and 2014, the global catch of skipjack increased 73%. We don’t know where the breaking point is and whether these stocks would even recover after a crash, like in the case of the Newfoundland cod, which was fished to just 1% of its preindustrial population in 1992 and may never fully rebuild. We can’t afford to keep making the same mistakes. We can’t let this well-worn story of depletion play out again, with greater and greater consequences for the ocean and for ourselves. We must listen to the science and history screaming at us to slow down. We must find a new way forward, and soon.

CCAMLR has the opportunity to both protect the Ross Sea in a near-intact state, and set the highest possible bar for fisheries management at the same time. Neither can be achieved without the other. A new study out this year shows that Weddell seals rely on toothfish to regain lost weight after pupping, a crucial time in their yearly cycle as they prepare for winter, and predicts a significant impact on Weddell seal populations under the current fishery management plan. This is the type of study that must come to bear on the management of the fishery and MPA. We need to strive for the best-managed fishery in the world, where the catch limits are determined by what is sustainable for the ecosystem as a whole. The opportunity is there, and CCAMLR has worked hard to build an organization to achieve just that. But CCAMLR must go further. Fisheries data and the theoretical models used to manage the fishery have been shrouded in secrecy, preventing independent assessments of the fishery and its ecosystem impacts. We need fully transparent policy. We need CCAMLR to openly share their data and fisheries models with the world. That information should belong to all of us. We need to craft a masterful blueprint of precautionary scientific management with more input from all the CCAMLR nations. We must immediately begin to monitor the health of the MPA ecosystem and the fishery with long-term research involving multiple CCAMLR nations. A proposed multi-national research and monitoring plan for the MPA was endorsed but not formally adopted in 2017. CCAMLR must achieve these goals if it is to succeed, and continue to lead the way to the conservation and truly rational use of our oceans. And we must pay attention and demand that CCAMLR succeeds.

Ross Sea MPA Map, Signed by CCAMLR Delegates. Courtesy: John Weller

The Ross Sea MPA comes into force today. It is one of our greatest achievements in the conservation of our oceans. I wish you could have witnessed the moment it happened. We must use this opportunity wisely. And the clock is ticking…