Stories of the Sea: Dark Vessels and Floating Utopias

By Safina Center Fellow Raffi Khatchadourian

The Sealand rig, a couple months after a fire in 2006. ©Richard Lazenby

“The year 1866 was marked by a bizarre development, an unexplained and downright inexplicable phenomenon that surely no one has forgotten.” So begins Jules Verne’s 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea, followed by reports of several mysterious collisions at sea. We are introduced to Captain Nemo’s unusual ship, the Nautilus, only indirectly—glimpsing its outlines, as it were, from the havoc it causes.

I thought of this recently while reading a paper in Nature, published earlier this year, by Fernando Paulo of Global Fishing Watch, and nine other colleagues. Their study examined many “dark vessels,” which mask their positions as they engage in commercial activity, like fishing and shipping.

The International Maritime Organization requires all vessels that are more than three hundred tons, and that cross national boundaries, to make their positions known with a device called an AIS transponder. But dark vessels, like Nemo’s submarine, seem to go out of their way to evade detection.

Paulo and his colleagues had identified them with the help of AI, as they analyzed two million gigabytes of satellite data from the European Space Agency that focus on global ocean traffic between 2017 and 2021. Tens of thousands of ships that were visible by satellite appeared to have their AIS transponders turned off, including, it seems, three quarters of the world’s industrial fishing fleet.

A map of dark vessel activity in North Africa, created by Global Fishing Watch through the use of Synthetic Aperture Radar (SAR) to image the earth’s surface. Copyright 2021, Global Fishing Watch, Inc. Accessed on 11/27/24. https://globalfishingwatch.org/research-project-dark-vessels/

There have been several investigations into dark fleets in recent years, by a number of different groups. In 2021, Oceana tracked hundreds of Chinese fishing vessels “pillaging the waters off Argentina and disappearing from public tracking systems.” But this year’s study is perhaps the most sweeping and detailed, revealing illegal fishing “hot spots” off of the Korean peninsula and in iconic protected areas, such as the Galapagos Marine Reserve and the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park.

Needless to say, these ghost fleets pose risks to ecosystems, and threaten local economies that rely on fisheries. Moreover, to the extent that they engage in lawless activity, they inevitably foster an atmosphere of abuse. Last year, Ian Urbina and The Outlaw Ocean Project published a stunning feature in The New Yorker, “The Shadow Armada,” capturing some of the violence used in illegal fishing; their story documents heartbreaking pleas for help from captive laborers on vessels that are very likely dark.

There is a larger context for such fleets in the age of the Anthropocene. The oceans are rapidly being depleted of megafauna for human consumption, and the more that they are depleted, the greater the incentive to break rules and laws, to harvest more of them. The Global Fishing Watch study touches on this larger issue, noting that its immense satellite dataset indicates a notable reduction in fishing activity overall—on a planetary scale. “Many countries that have reformed their fisheries have shown an actual decline in their fishing effort,” the authors write. “The decrease highlighted in this study may reflect this longer trend and we may have already seen the peak of fishing activity in the past decade.”

While we are on the subject of ocean lawlessness (or freedom), I’ll confess that I can’t get enough of stories about people fleeing to the seas, hoping to escape the rules of civilization. So I was thrilled to see “60 Minutes” re-air its 2023 feature on the Principality of Sealand, an aspiring micronation, “founded” in 1967 on a decommissioned North Sea platform that the British military had built during World War II. By the time the “60 Minutes” crew left the rusting platform, Sealand’s self-proclaimed monarch, Prince Michael Bates, had bestowed upon the correspondent, Jon Wertheim, a royal title.

The Sealand experiment always seemed, to me, to hover somewhere between irony and earnestness. But, more recently, “seasteading”—the libertarian dream of building stateless ocean utopias—has been explored seriously by people, like Peter Thiel, with money from Silicon Valley. Online, you won’t have trouble finding Jetsons-like computer-generated plans for futuristic floating cities, but two real-world experiments have proven to be gritty failures—ending in loss and death.

One of those experiments is expertly documented in a recent feature published by the FT, titled, “The fake hitman, the crypto king and a wild revenge plan gone bad.” It recounts the long crazy saga of a floating “pod,” anchored fourteen miles off the coast of Thailand. Its builders hoped that the structure would be a haven from taxes and state control, and the article relays this with many vivid details—for instance that “the pod was christened XLII, or 42 in Roman numerals, a reference to Douglas Adams’ The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy, in which the number is said to be the answer to the meaning of life.” In 2019, the Thai military raided the structure, the project collapsed, and its inhabitants fled.

The other experiment ended more tragically, and its story has not yet been fully told. It centers on an Italian fugitive, Samuele Landi, a telecoms entrepreneur who fled Italy more than ten years ago, around the time he was being charged with fraud, in two separate cases. (The Italian courts reportedly convicted him in both.) He landed in the United Arab Emirates, where he became the Liberian consul, and, according to one extensive investigation, facilitated a controversial deal that involved selling a million hectares of Liberian forest to a carbon offset company owned by a Emirati sheikh. (He also became the general manager of a firm claiming to make phones with “military-grade encryption.”)

Eventually, Landi began living on a barge anchored between Iran and the U.A.E., and at some point, he decided to sail it hundreds of miles to a seamount off the coast of Madagascar, and use it as a nucleus to build a “libertarian state” out of similar barges that he planned to lash together. “The idea is to create place where people can stay without being subject to the matrix,” he explained to a journalist—or as Captain Nemo says of the sea, “There is only independence! There I recognize no masters!”

The barge never made the crossing. It capsized this year. Landi perished. But before the sinking, he vowed to a filmmaker that he was done with land. “I will die at sea,” he said. “I am not going back.”

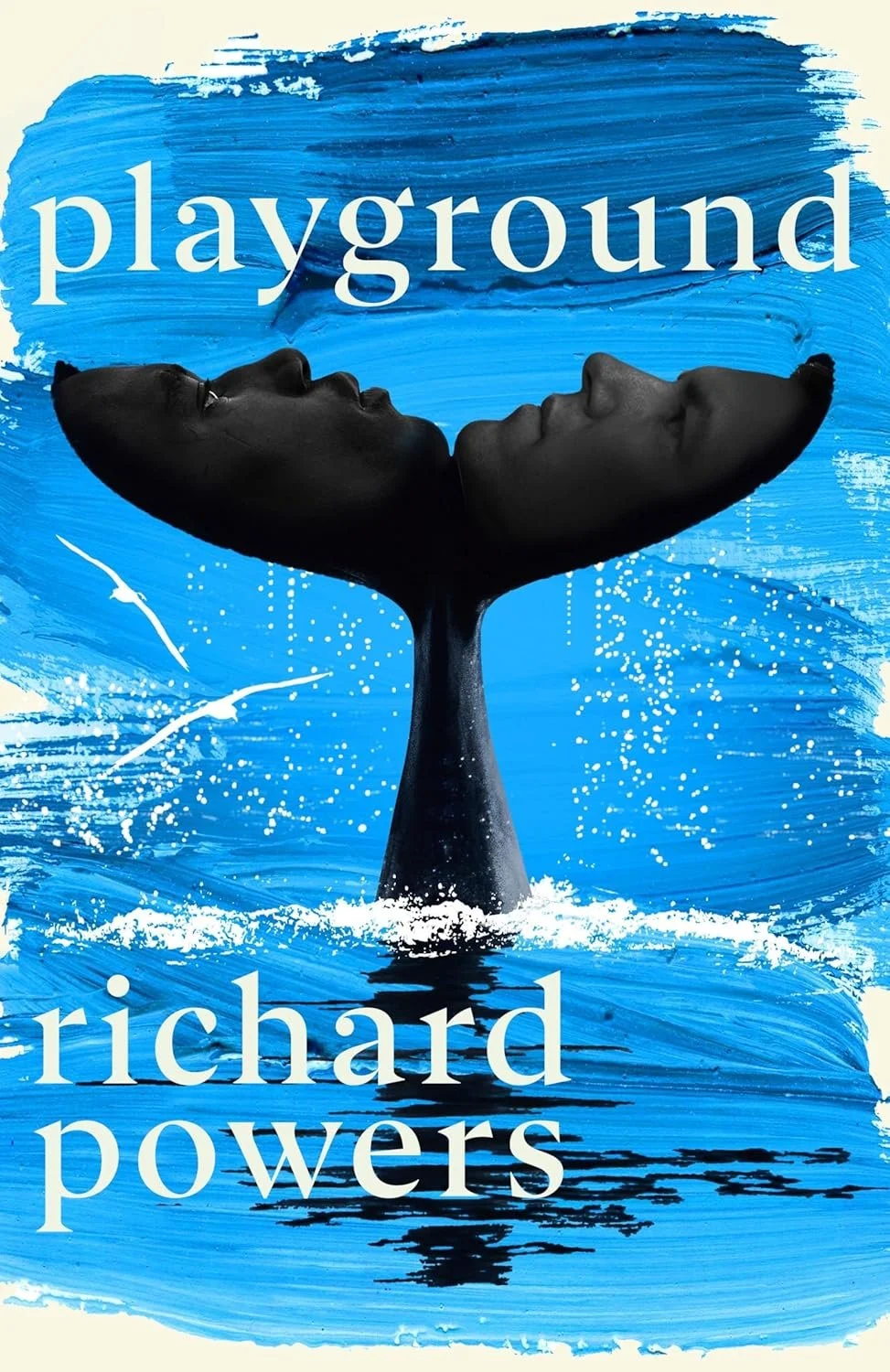

Floating utopian communities. Ocean ecology. Humanity’s drastic diminishment of the natural world. All of these themes come together in the new Richard Powers novel, Playground, which was released this September. The book has been described as “a cyberpunk thriller of sorts, an Anthropocene novel, an oceanic tale and an allegory of post-colonialism.” Six years ago, Powers wrote a novel called The Overstory that reshaped the way many readers thought about trees (to the extent that they had given any thought to trees before). It won a Pulitzer. Will this new book have the same effect on people’s views of the oceans? It is fiction, but sometimes fiction can affect popular understanding more potently than the detailed work of scientific inquiry. The Guardian, in its review of Playground, notes, “Some of the underwater scenes are so limpid and sensorily rich, it’s like watching an oceanic feature in Imax; throughout, there’s a quasi-spiritual appreciation for the wonders and mysteries of marine life.”