So you live near a coral reef: Why experts say that’s not good news for reef conservation

By Erica Cirino, Safina Center Launchpad Fellow

My favorite beach on Long Island’s North Shore, where I live, is more than 700 miles away from the nearest coral reef (in Bermuda). This distance may be a good thing: Recent research suggests the further a coral reef is from human civilization, the better. (To get close from far away, check out these reef cams.)

Last month a global group of ocean researchers published a paper in Ecology Letters explaining the relationship between coral reefs’ proximity to people—measured in travel time to major marketplaces—and reef health. They write that the closer a reef is to a high-density human population center, the less likely large and diverse fish populations are likely to call it home. They found that fifty-eight percent of the world’s coral reefs are located within 30 minutes of a human settlement, and thus harmful human activities.

“There is substantial evidence from around the world that coral reefs are being degraded from human activities such as fishing, pollution and climate change,” says Dr. Joshua Cinner, a professorial research fellow at James Cook University in Australia and lead author of the paper.

Additionally, Cinner says, the more accessible a coral reef is to a population center, the less likely it is to be protected under strict marine conservation rules—and this isn’t good for anyone. “There are tens of millions of people who directly depend on reefs for their livelihoods, and many times that who depend on the fish that reef provide, the protection they offer shorelines and the cultural values they provide.”

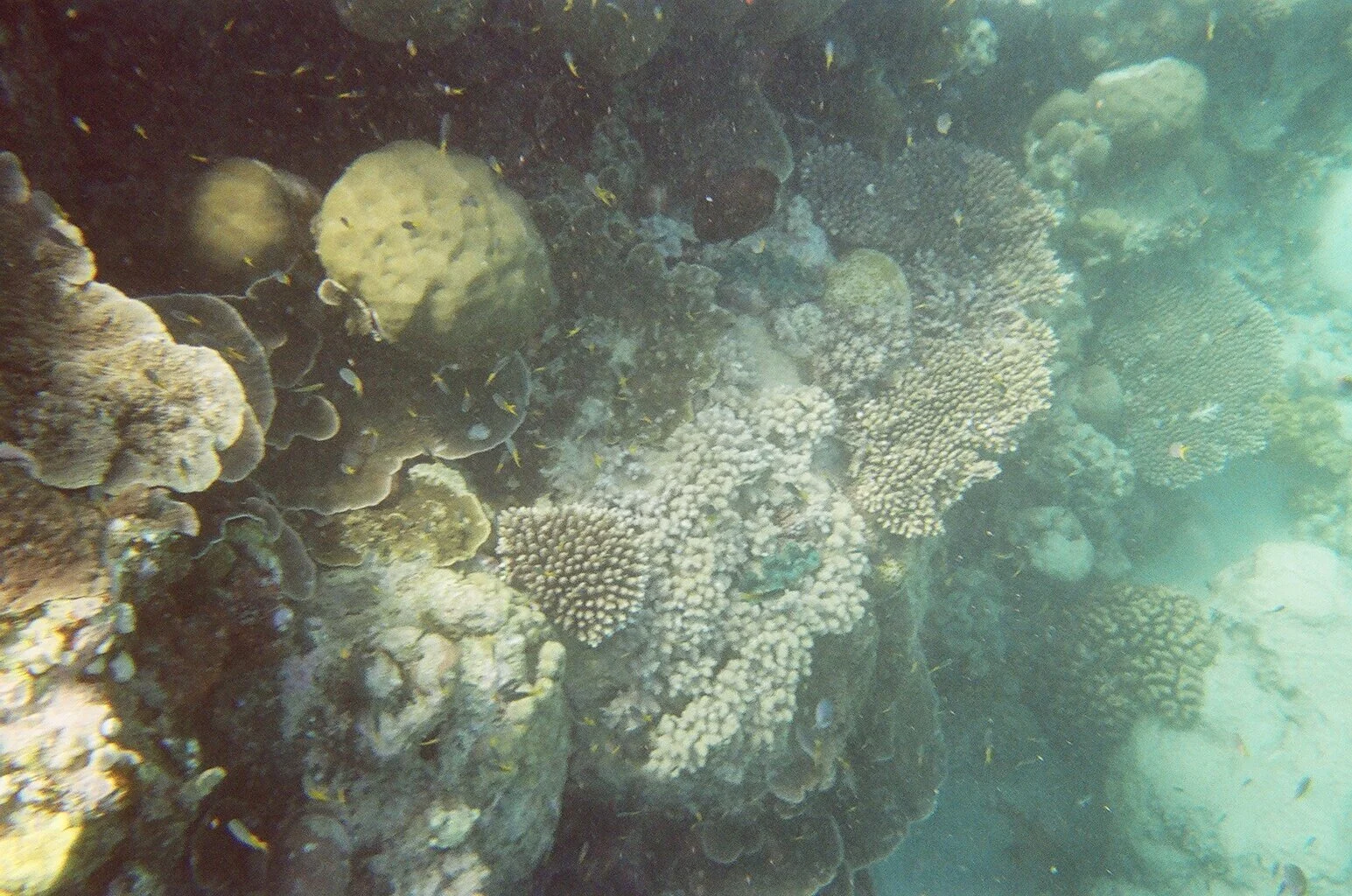

Results of overfishing and bleaching on Australia’s Great Barrier Reef, which is considered an “accessible” reef. Photo: Jorge Láscar

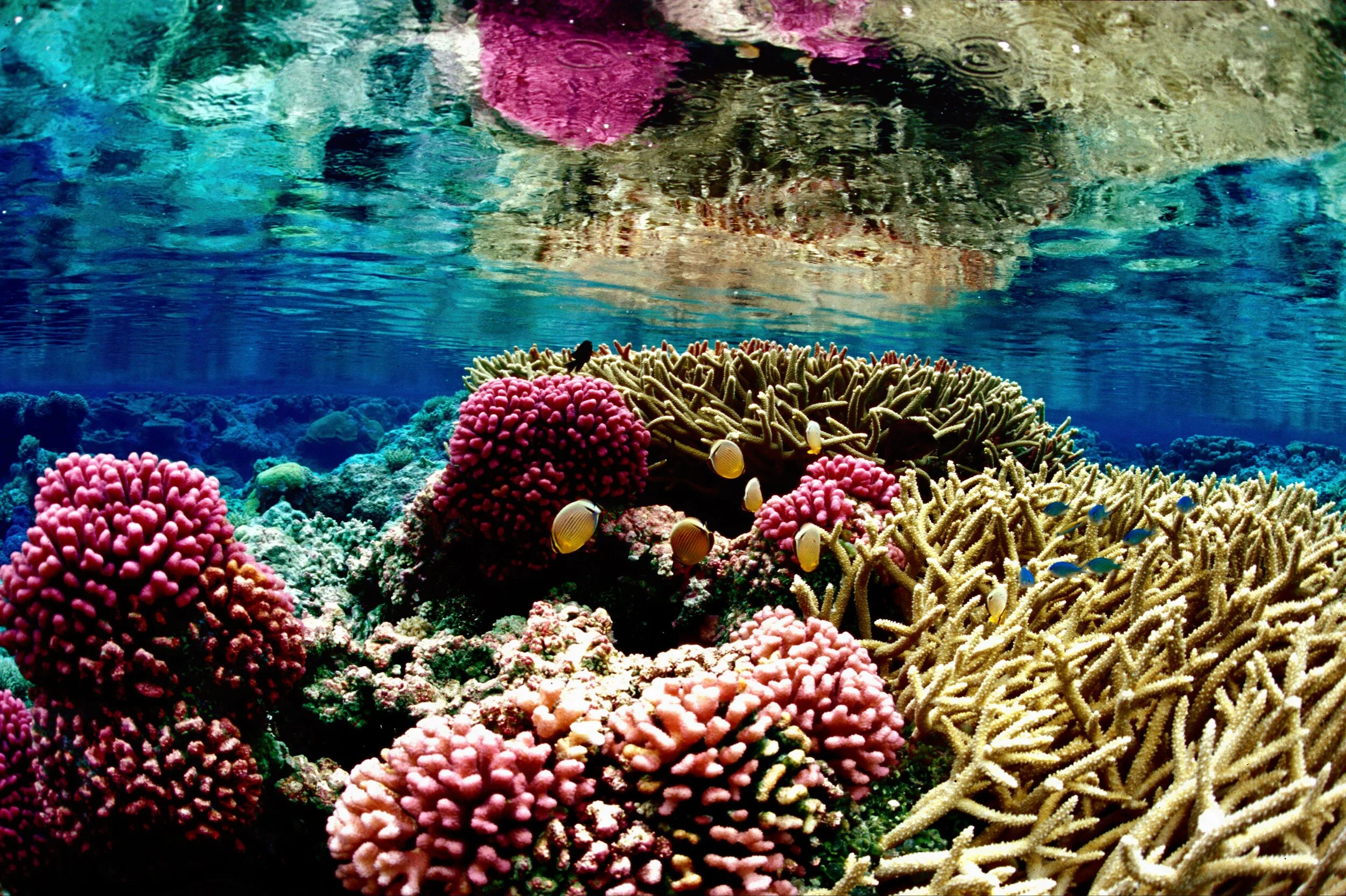

The colorful, thriving coral reef at Palmyra Atoll National Wildlife Refuge is an example of an less “accessible” reef, thus it’s less affected by human actions. Photo: Jim Maragos/U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service

Cinner became interested in studying the connections between humans and coral reefs in 1996 while working as a U.S. Peace Corps volunteer in the Montego Bay Marine Park in Jamaica. There he saw dying reefs overtaken by algae—a result of overfishing, which was a result of poor ocean management. He realized some of the park’s conservation efforts were failing because they didn’t best reflect the needs and lifestyle of the local people whose lives were closely intertwined with reefs and the creatures they support.

On this particular project, Cinner and his group worked off the premise that natural resources most accessible to people tend to be most at risk of degradation. This is an idea often used when determining the environmental affects of human activities on land, such as building roads or falling trees. However, it’s never been applied in research on ocean conservation, much less on coral reef ecosystems.

To determine what human proximity means for reef health and conservation, Cinner’s group analyzed fish population estimates as well as maps of reefs, marine protected areas and nearby human civilizations.

He says he’s noticed that human proximity often impedes useful conservation efforts because conflicts for limited space and resources are more likely to arise between those who have a stake in reefs, from environmentalists to fishers to tourists. Reefs further from human settlements tend to be more protected because few or no people regularly have access to them, so fewer conflicts occur.

According to Cinner, marine reserves aren’t necessarily a great approach to ocean conservation, since they remove the human element of the reef-protection equation.

“Considering that people are an integral part of the seascape in most reefs globally, we have to change this mentality,” says Cinner. “We need to better understand the human dimensions of reefs if we are to effectively manage them- this includes understanding peoples values, aspirations, and needs and how these influence the ways they use and manage reefs.”

Dr. Elizabeth Brown-Hornstein, Safina Center research scientist and sustainable seafood program director says Cinner’s research promotes some interesting new approaches to coral reef conservation.

“Most of the small-scale coral reef fisheries in developing nations have little data and little management,” says Safina Center Dr. Elizabeth Brown-Hornstein, Safina Center Research Scientist and Sustainable Seafood Program Director. “I definitely think that collaborating with fishermen and the communities will be crucial for collecting better data and successfully implementing conservation initiatives.”

You can aid coral reef conservation by:

practice responsible diving and snorkeling – do not touch or anchor your boat on reefs

eating sustainable seafood – opt for more abundant seafood species not caught on or near reefs

reducing your use of plastic products and always recycling plastic trash (instead of throwing it away)