Salmon Return to the Salmon

By Paul Greenberg, Safina Center Fellow

On Paper Mill Road in Colchester, Connecticut, the paper mill has just been removed. And because of its removal, salmon just might return to the Salmon River.

Photo: Paul Greenberg

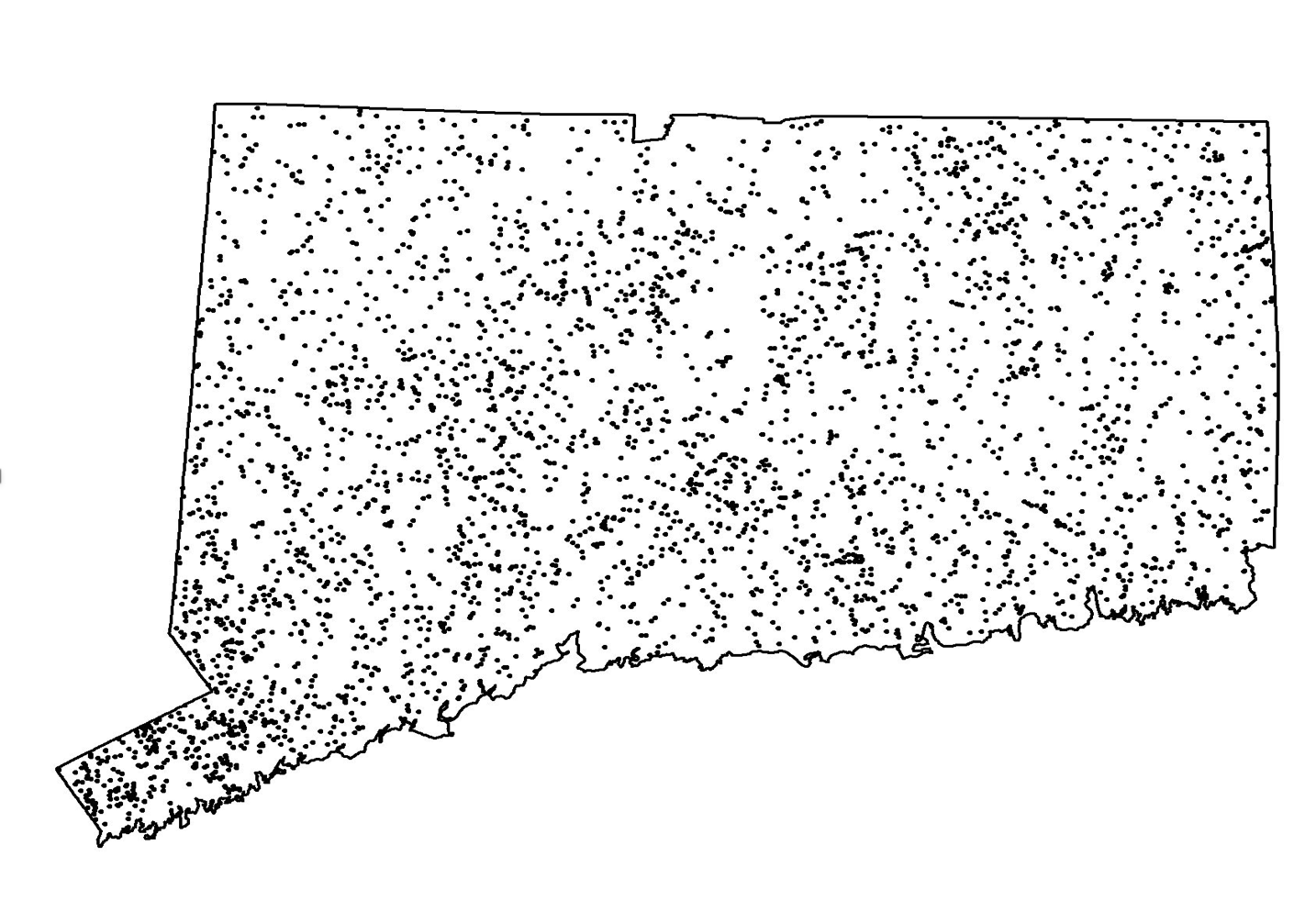

I have been following the story of the Salmon River watershed for close to a year now. I first visited a modest tributary of the Salmon called the Jeremy River last November. There on a cool fall day I watched as a hoe ram beat away at a concrete dam that had blocked the passage of salmon and other anadromous fish for over 150 years. It is one of over 4000 dams in the state of Connecticut that today don't serve much purpose. The Norton dam on the Jeremy had once powered a mill that had produced particle-board for book bindings, women's shoe heels and buttons. But with manufacturing long gone from the post-industrial northeast, the only thing the milldam did in recent decades was block fish. The Jeremy merges with the Blackledge River to form the Salmon River, which in turn merges with the Connecticut River and then heads out to the Long Island Sound. If the Jeremy dam could be removed sea run fish would have a much better chance of completing their epic life cycles that once took them as far away as Greenland.

Jeremey River (before, with dam). Photo: Paul Greenberg

Jeremy River (after, with dam removed). Photo: Paul Greenberg

The dam removal had been organized by a partnership spearheaded by Sally Harold of the Connecticut chapter of the Nature Conservancy. Sally along with Connecticut's Department of Energy and Environmental Protection had worked with the dam's owners for years to come up with a plan for taking out the structure. The dam's final removal was as the matriarch of the Norton family, Nan Wasniewski put it, "bittersweet.” The mill had once employed and anchored a community. The millpond behind it had been a swimming hole where Nan remembers plunging in as a girl. But Nan recognized that times had changed and that the dam was much better off being remembered than maintained. It had become a flood risk and an insurance liability — something that government agencies are starting to recognize. Indeed it was Federal a Hurricane Sandy Resiliency recovery grant administered by the US Fish and Wildlife Service, which made the $700,000 removal project possible.

Map of dams in Connecticut. Courtesy: Paul Greenberg

When I returned to the Jeremy River this past September for a ceremony to celebrate the newly restored river passage, I was astonished to see how much the river had changed with the dam out of the way. Earlier, a slow-moving, murky pond supported a mostly invasive community of bluegills and bass. Now sparkling riffles bounced over rocks and oxygenated a clear cool stream. Steve Gephard of Connecticut's Department of Energy and Environmental Protection, one of the nation's premiere dam busters, marveled how when they'd sampled the river in August they'd found that a "classic New England riverine fish community had returned." Black nosed dace, white suckers and sea lamprey all abounded.

But what was most encouraging about the river's restoration was the presence of Atlantic salmon. Shortly after the dam removal in November, Steve Gephard organized a stocking of Atlantic salmon juveniles (tiny fry) into the Jeremy. During electroshocking surveys several months later they found the salmon parr everywhere. Hiding behind boulders, playing over cobble, lurking beneath undercut stream banks.

Atlantic salmon parr. Photo: Paul Greenberg

Now as the ceremony concluded, Steve Gephard and Sally Harold carried a cooler holding roughly two dozen salmon parr down to the river's edge. The young salmon were parsed out to different people who had made the project possible, including Nan Wasniewski who had given the final go ahead to remove her family's ancestral mill and dam. Spry and white haired Nan dipped a net down into the river and watched as several parr ventured out into the current. Then handing the dip net to Sally Harold loaded with one last salmon juvenile Steve Gephard made one last dedication.

Parr in cooler. Photo: Paul Greenberg

Steve Gephard on Banks of Jeremy River. Photo: Paul Greenberg

Wasniewski releasing salmon. Photo: Paul Greenberg

"Once these fish go into the river, they'll start to blend in with the surroundings. They'll become wild fish and you won't even be able to see them anymore. And, since they're wild we're not really supposed to give them names. But I think it's appropriate in this instance to call this fish 'Sally'."