Project Pisces: Hidden ecosystems and lasting legacies

By Jessie Perelman, Safina Center Launchpad Fellow

Exploring the deep ocean is by no means a simple task. It is the great frontier, the endless unknown about which we know so little. Broadly defined as the ocean and seafloor lying below 200 meters, the deep sea is by far the largest biome on Earth covering well over half of the surface of the planet. Yet, less than 5% of this global habitat has ever been investigated, due in large part to the inaccessibility of this hostile space where extreme pressures, low temperatures, and near darkness dominate. So how do scientists study the deep sea? Great advances in technology over the last century have enabled researchers to have a presence at depths far beyond those attainable by traditional scuba diving. Since the creation of the first practical bathysphere in 1934, manned submersibles have evolved as one of the most effective tools for deep-sea exploration, bringing crew and scientists to depths several thousand meters below the ocean’s surface.

Pisces V (left) and Pisces IV are three-person research submersibles operated by the Hawai’i Undersea Research Laboratory. These human operated vehicles bring researchers to maximum depths of 2,000 meters to explore the deep sea from the deep sea itself. Photos: Emily Young, Jessica Perelman

The Subs

Two such submersibles lead oceanographic research and exploration efforts in the Pacific Ocean, operated by the Hawai’i Undersea Research Laboratory (HURL) at the University of Hawaii. Pisces IV and Pisces V are battery-powered, three-person vehicles that have successfully completed expeditions to a maximum working depth of 2,000 meters since 1981. With a highly efficient system of launching, tracking, and recovering the subs aboard the R/V Ka‘imikai-o-Kanaloa (KOK), the HURL team and collaborating scientists are able to collect hours of video footage, environmental data, and specimen samples from seafloor habitats. Operating two vehicles at once allows for twice as much data collection and affords a backup safety capability if either submersible should ever need emergency support. Each Pisces dive lasts between 7-9 hours, during which time the pilot and two trained observers can survey a given area at depth with their very own eyes- an observational asset that cannot be surpassed.

The project

The latest mission of this deep submergence program, funded by the National Science Foundation, was a project of great national importance, and certainly a career highlight for HURL. Led by principal investigators Amy Baco-Taylor (Florida State University) and Brendan Roark (Texas A&M University), a team of scientists set out to assess the recovery of seamount ecosystems within and around the Papahānaumokuākea Marine National Monument from years of fishing and bottom trawling. What the group discovered from a compilation of 76 dives was shocking. In comparison to ‘pristine’ seamount habitats observed within the protected national monument, those that are still fished in unregulated international waters, or that have been in recovery for 40 years, presented with mass amounts of trawling gear, nets, and fishing line that have destroyed ancient corals and seamount habitats. Large gold corals, many estimated to be upwards of 1,000 years old, were found uprooted and dead having been raked-over by industrial fishing gear at several of these locations.

One of many fishing gear entanglements discovered in the northern Pacific Ocean, particularly along the Hawaiian-Emperor seamount chain. Photo: Terry Kerby

Some sites did show signs of revival, however, including the Hancock Seamounts which have been protected from international fishing pressures for several decades and now reside within the monument. Large “no-take” marine reserves like Papahānaumokuākea, which is currently the largest on the planet, have proven very effective against mass depletion of fish stocks and destruction of seafloor ecosystems. However, the current administration is pushing to repeal federal protections of several of these monuments and re-open them to fishing. As evidenced by the images gathered from this deep-sea coral recovery project, such actions would have major repercussions for the fragile organisms and habitats already devastated from years of overfishing. These results will hopefully influence efforts to expand, rather than retract, the boundaries of Papahānaumokuākea and other marine protected areas.

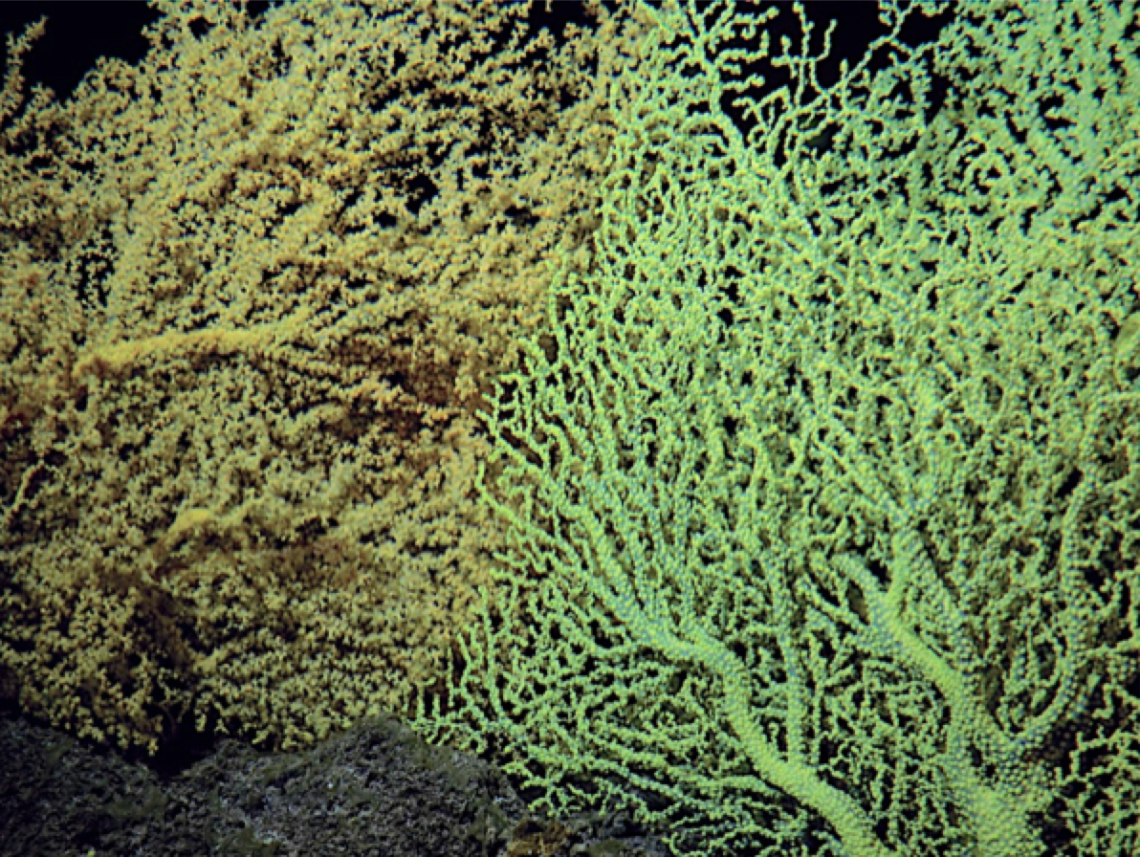

Massive gold coral trees such as these were found on several seamounts and likely live to be several thousand years old. Photo: Jessica Perelman

The scientists

In addition to the success of these dives in revealing the hidden ecosystems of more than a dozen undersea mountains, a remarkable aspect of the whole endeavor was the challenge it posed to the status quo. Except for one principal investigator, the entire science team conducting the field work on this project was female. Not only that, but most of these researchers are very early in their careers as undergraduate and graduate students. To watch a group of young women call the shots and take leadership of such a significant scientific effort is a testament to the strength and capability of women in STEM. Rarely did anyone aboard the KOK ever question the decisions or ideas posed by this talented and strong-minded group. “You [all] are the future of oceanography and Earth science,” were the inspiring words imparted by one of the long-time Pisces pilots, Maximilian Cremer.

Seven young female scientists led field efforts on the latest HURL expedition, each acting as observers on multiple dives in the Pisces submersibles to depths greater than 750 meters. From left to right: Savannah Goode, Nicole Morgan, Danielle Schimmenti, Julia Andrews, Allison Metcalf, Melissa Betters, Jessica Perelman. Photo: Julianna Diehl

“It was an incredible experience to be able to collaborate with such intelligent and motivated women every day,” said Julia Andrews, a recent graduate of Florida State University who was part of this last expedition and participated in several sub dives. “Our presence on the ship was inspiring because it was a physical example of how women are breaking down the barriers and stigmas thrown against us in the field,” she said. There is no doubt that this experience and the responsibilities that came with it have established ambition and passion for this new generation of researchers.

Fate of the Pisces?

The recent expeditions come at a critical time not only for the sake of marine protect areas and early career scientists, but for the current and future existence of manned seafloor exploration. Upon completion of the last research cruise, the University of Hawaii announced their decision to terminate operations of Pisces IV and Pisces V and their designated mothership, R/V Ka‘imikai-o-Kanaloa.

Required maintenance for R/V Ka‘imikai-o-Kanaloa, the support ship for the Pisces submersibles, will cost about $2 million. Without a fast solution to this funding issue, the two subs may have completed their last dives with the Hawai’i Undersea Research Laboratory. Photo: Jessica Perelman

At a time when remotely operated vehicles (ROVs) are becoming more popular as tools for deep-sea exploration, manned submersible use seems to be falling out of favor. However, unlike the subs which can access areas of difficult terrain and maneuver around, say, extensive fields of fishing gear as observed during the latest dives, ROVs must remain tethered to a ship at the surface and can become easily damaged or entangled. This is not to say that one tool should exist without the other. Both manned submersibles and ROVs are essential assets needed to study deep-sea environments, each with their own strengths and weaknesses. Unfortunately, funds are tight and the university cannot cover the required $2 million needed for mandatory maintenance of the KOK and refits for Pisces IV. Barring a generous donation in the immediate future, the fate of the only deep submergence program in the Pacific Ocean lies in question.

Launching Pisces V with ease on a calm day. Photo: Steve Price

Alongside Cremer, chief pilot and HURL operations director Terry Kerby has kept the program alive and running for years and is currently investigating all possible options. “I have not given up hope to keep these subs diving,” he says.