Plastic: The big breakup

By Erica Cirino, Safina Center Launchpad Fellow

My dog Foosa and I step onto the beach, and in the first few steps I find—as usual—something made of plastic. This beach is strewn with everything from fiberglass buoys to crumbling Styrofoam cups to poorly disposed “disposable” lighters to plastic bags (use once, throw away, except that “away” is here). Today the big find is a barnacle-encrusted red buoy.

Foosa the Alaskan malamute sitting on buoy. Photo: Erica Cirino

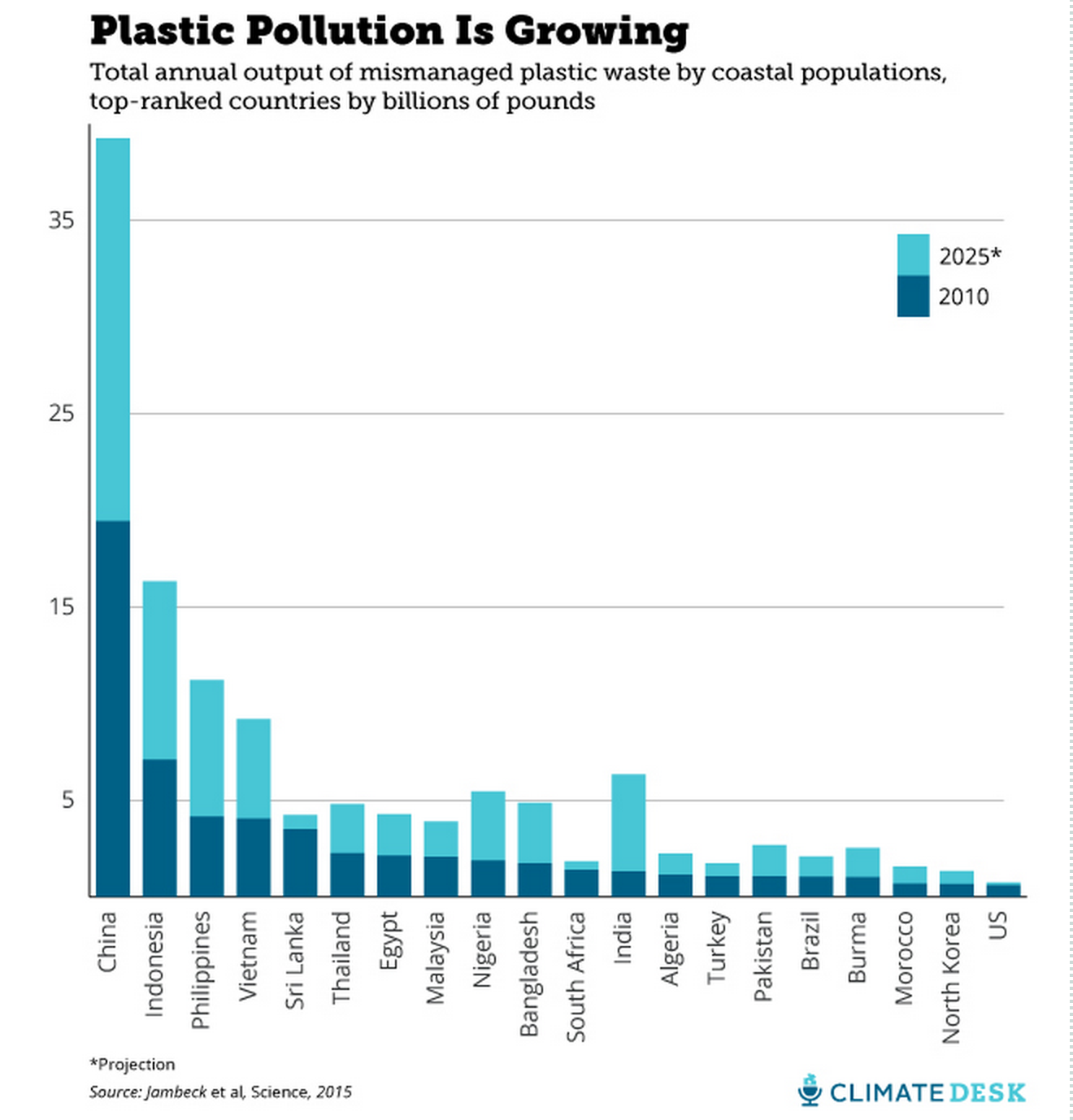

This is not an isolated sighting: On beaches all over the world, from the coasts of suburban Long Island—where I live—to the remote shores of Alaska, plastic has made its unwelcome appearance. More than a trillion pounds of plastic find its way into the environment every year.

But more alarming than the plastic trash I can see is that which I cannot. As I’ve written previously, plastic items floating in the oceans break up into tiny pieces, which are easily ingested—mostly by fish, bivalves and crustaceans, but also by animals and people. Scientists have found that these bits of plastic cause reproductive and metabolic problems in oysters and other marine life, and even humans.

Unlike other types of trash—say, apple cores or newspapers—scientists believe it will take hundreds to thousands of years before it completely decomposes (since synthetic plastic has only been around since 1907, they’re not sure exactly how long it takes, or if it ever will go away). Instead of breaking down it continually breaks up into smaller pieces.

Take a plastic bag, for instance. Experts estimate that people across the world use more than a trillion single-use plastic bags every year. On average, these bags are used for just 12 minutes to carry groceries, takeout and other items before they’re tossed in the trash—or worse, directly into the environment.

Let’s say this bag escapes from a trashcan sitting on the street: The wind blows it from the can into a tree, across an open soccer field and into a river, where the strong water current carries it into an estuary. Then the bag floats into the ocean.

With ocean covering more than 70 percent of Earth’s surface, it’s not too surprising that this is a popular place for plastic trash to accumulate. Whole bags can harm marine life—especially creatures like sea turtles, which often mistake plastic bags for a favorite snack: jellyfish. Plastic are also deadly delicacies to albatross, which infamously consume huge quantities of plastic bags and other plastic trash.

But this bag doesn’t get eaten. Instead it floats around in the water until ocean currents carry it into a bigger gyre of plastic trash. Thanks to chemistry and the physical churning of the ocean waves, that’s where it begins to break up.

First sunlight gives plastic the energy it needs to absorb oxygen from their air and ocean water. This weakens the bonds between each plastic molecule, making them separate from one another. So that bag turns into dozens brittle shredded plastic scraps.

Over time, waves break these scraps into smaller bits, until the plastic bag is transformed into hundreds of thousands of microscopic plastic pieces. Plastic does some of its biggest damage when its at its smallest, readily absorbing toxic chemicals in ocean water and being consumed by marine creatures (and thus, humans) who are forced to bear the brunt of plastic’s damaging health effects.

Thanks a lot, plastic bag.

“That one little bag blowing in the wind may not seem like a big deal,” says Rhonda Sherman, an N.C. State University extension specialist who has been working in the solid waste field for more than 30 years. “But plastic never really goes away. Despite it being labeled as ‘disposable,’ plastic is not a product you should be regularly using and throwing away anything made of plastic.”

At N.C. State, Sherman advises and educates companies and consumers about solid waste management and the concept of sustainability, or meeting the world’s present needs without harming the well-being of future generations.

Plastic, says Sherman, is inherently unsustainable. “My first message to people is to use reusable items whenever possible. If you must use disposable items out of convenience, then make sure they’re labeled ‘compostable’ and have B.P.I. certification.”

And most importantly, don’t litter, says Sherman. She’s traveled the world and one thing that’s constant is plastic trash in the environment.

Recently Sherman traveled to Santo Domingo, Dominican Republic, a place that has pristine beaches and crystal-clear waters, according to travel catalogues and TV ads. Sherman walked to the beach near her hotel one morning and what she saw was “shocking.”

“I couldn’t set foot on it—the shoreline was so covered in trash, completely plastic,” she says. “I figure that they must Photoshop all that plastic out of photos to attract tourists!”

Plastic pollution prevails even back home in the States. But education, good recycling programs and incentives like plastic bag bans and bottle deposits can do a good job of reducing the amount of trash in the environment.

Sherman has seen the benefits of container-deposit legislation in her home state of Michigan. There, a plastic bottle (or glass, metal, paper or combined-material container) under a gallon earns you a dime. So instead of throwing their recyclable trash away—or worse, out of their car windows—people return bottles to earn cash.

Container-deposit, plastic bag and Styrofoam legislation is an important part of the equation when it comes to preventing more plastic from contaminating the oceans. But the bottom line is every person needs to stop using plastic items.

I don’t know about you, but I’m ready for my big breakup—with plastic, that is. I’m in support of Intro. 209-2014, a bill that would impose a 10-cent fee on plastic bags in New York City; the recently passed Microbead-Free Waters Act of 2015, which prohibits manufacturers from including tiny plastic microbeads in their products; and for using reusable (or at least compostable) bags, mugs, thermoses, containers and cutlery. Are you?