Most problematic types of derelict fishing gear

By Eric Gilman (Safina Center Scientist in Residence), Michael Musyl, Petri Suuronen, Milani Chaloupka, Saeid Gorgin, Jono Wilson, Brandon Kuczenski

The days of using natural materials for fishing gear components are largely over. Since the mass production of plastic products began in the 1950s, most of our products—including fishing gear—are made of plastic. Every year, about 10 million metric tons of plastic enters the oceans from the land and sea. Without drastic changes, this amount is expected to substantially increase over the next decade.

Fishing gear becomes derelict when fishers abandon, lose or discard their gear at sea. With increased fishing effort, expansion of fishing grounds and increased use of synthetic and cheap materials, the amount, distribution and adverse effects of derelict gear have likewise increased. As is the case with many plastic items, fishing gear represents yet another example of the short-term and linear use of a plastic product.

Photo: Derelict pot, Persian Gulf. © Saeid Gorgin.

Unlike other forms of marine debris, derelict fishing gear, produced by the world’s 4.6 million fishing vessels, is designed to catch marine life. Under certain conditions, derelict gear can continue to catch and kill organisms for decades. This ghost fishing affects vulnerable species such as sharks, rays, seabirds, marine mammals and marine turtles; other non-commercial species; as well as principal market species that are targeted by the fisheries. While ghost fishing is the most politicized adverse consequence of derelict gear, it causes other serious problems, including distributing and transferring toxins and microplastics into marine food webs; transporting invasive, non-native species; distributing microalgae that may cause harmful algal blooms; altering and damaging coastal and marine habitats; obstructing in-use fishing gear and navigation; and reducing the socioeconomic value of coastal and nearshore areas. In marine environments below the sunlit photic zone, especially on the deep seabed, plastics can persist—with a small amount of breaking down.

Photo: Derelict gillnet, Hawaii © Frank Baersch, Marine Photobank

Despite a recent surge of attention to derelict fishing gear, surprisingly, there is extremely limited and highly uncertain information available on the magnitude and effects of derelict gear and other sources of marine debris. Embarrassingly, a crude, several-decades-old estimate of the annual production of derelict gear is still cited today as the best available global estimate, while more recent estimates of loss rates are available for only a few gear types and regions, with extremely low certainty. Substantially more robust and contemporary estimates of gear-specific rates, magnitude and adverse effects of derelict gear are needed to serve as a benchmark against which to measure the performance of management interventions.

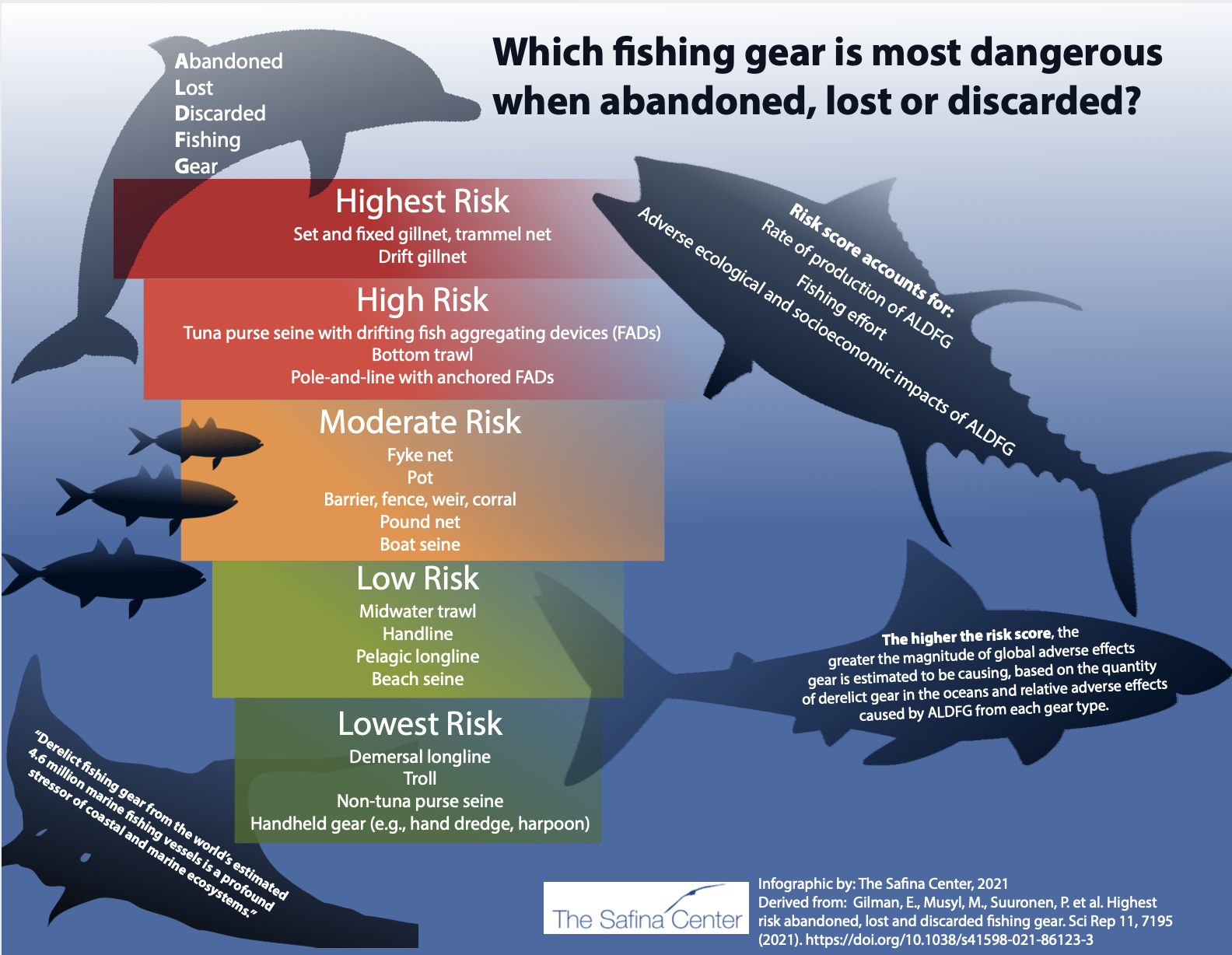

To contribute to filling this priority knowledge gaps, an international team of scientists conducted a study published today in the journal Scientific Reports, which can be downloaded by clicking here. Our research team produced a rank-order of fishing methods based on:

Derelict gear production rates – what percent of gear that is used for fishing ends up abandoned, lost or discarded into the oceans.

How prevalent is the gear type – how much of the gear type is used globally, estimated from available data on catch weight and area of fishing grounds.

Adverse consequences from derelict gear – how big a problem does a typical unit of derelict gear (e.g., 1 sheet of gillnet, 1 fragment of bottom trawl net, 1 pot, 1 fish aggregating device) from a fishing method cause due to: (a) ghost fishing, (b) transfer of microplastics and toxins into food webs, (c) spread of invasive non-native species and harmful microalgae, (d) habitat degradation, (e) obstruction of navigation and in-use fishing gear, and (f) coastal socioeconomic impacts.

So, the first two components of this comprehensive risk assessment framework estimate the relative magnitude of derelict gear from each fishing method, while the third component estimates how serious the adverse ecological and socioeconomic adverse effects are from derelict gear produced by that fishing method.

The infographic, below, summarizes the main finding. Gear types of hand dredges, harpoons, spears, non-tuna purse seine and troll were least problematic. Globally, mitigating derelict gear from the following four fishing methods of greatest concern achieves maximum conservation gains:

Set and fixed gillnet and trammel net

Drift gillnet

Tuna purse seine with drifting fish aggregating devices

Bottom trawl

To curb derelict gear at regional and local levels, priorities will account for which fishing gears are predominant and the current fisheries management framework. A study of regional fisheries bodies found that over a third had not adopted relevant measures and few derelict gear mitigation methods were being tapped by the bodies that had adopted binding controls (Marine Policy 60: 225-239; 2015). Improvements in derelict gear controls are needed at both regional and local levels. In general, mitigation measures should follow a sequence of first avoiding and minimizing the production of derelict gear before considering activities that remediate adverse effects of derelict gear once it is already produced, and compensation for adverse impacts that could not be avoided, minimized and remediated. It is more effective to avoid and minimize producing derelict gear than to conduct remediation, such as locating and removing derelict gear and using less-durable and biodegradable gear components to reduce the duration of ghost fishing efficiency.

Locally, effective derelict gear mitigation measures are determined by the underlying causes of gear becoming derelict in that particular fishery and the fisheries management system. For example, Indonesia’s archipelagic water tuna purse seine, handline and pole-and-line fisheries fish on about 7,500 anchored fish aggregating devices (FADs, called rumpons in Indonesia). There is low compliance with government registration requirements and high loss from a variety of causes, including storms, vandalism, vessel collisions and old/worn mooring lines breaking. Gear marking is a common approach prescribed to curb derelict gear, most recently in the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nation’s Voluntary Guidelines on the Marking of Fishing Gear. While gear marking to identify ownership holds very little promise to mitigate gear losses in Indonesian anchored FAD fisheries, low-cost electronic technologies to detect real-time position and moorage breakages, and a voluntary industry anchored FAD fleet communication program might be effective approaches. Gear marking also has limited capacity to address the widespread abandonment of drifting FADs deployed by tuna purse seine fisheries, where wholesale changes in FAD management are overdue to stop the largely accepted practice of abandonment when the gear drifts outside of fishing grounds, including into unauthorized (illegal) areas. Conversely, gear marking, including using passive radio frequency identification or RFID tags, has been used effectively for compliance monitoring in pot fisheries with individual vessel pot limits where tags can be monitored through human observer and electronic monitoring programs.

Effective controls alone will not adequately mitigate derelict gear. As is the case for most fisheries conservation deficits, solutions to derelict gear require long-term investments that result in at least one but ideally both: (1) all components of governance systems being robust, including monitoring, controls, surveillance and enforcement; and (2) strong market-based incentives for improved environmental performance, including in managing derelict gear. Unfortunately, both are lacking in most fisheries. This is why compliance with international and local measures on derelict gear, including the International Maritime Organization’s MARPOL Annex V Regulations, Article 8 of the Code of Conduct for Responsible Fishing of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, and measures adopted by regional and national fisheries management authorities, is understood to be extremely poor in most commercial fisheries. For example, a gear marking pilot in a southeast Asian gillnet fishery found that the low value of the gear and a government program that was distributing free gillnets to promote development of the fishery resulted in low incentives for fishers to prevent and remediate derelict gear—under these circumstances, adding tags to the gear to identify the owner of derelict gear is unlikely to incentivize fishers to implement measures that would reduce high gear loss rates. The rudimentary governance framework and lack of demand for sustainably sourced seafood in the supply chain for most southeast Asian coastal gillnet fisheries require substantial, complex changes to incentivize improvements in gillnet fishers’ behavior that is causing high rates of gear to become derelict.

To assess the performance of global management of derelict gear using the framework established by this study, substantial deficits in monitoring and surveillance of fisheries’ waste management practices must first be addressed. For instance, of 68 fisheries that are managed by regional fisheries management organizations, 47 lack any observer coverage, half do not collect monitoring data on derelict gear, and most have rudimentary or nonexistent surveillance and enforcement systems (Fish & Fisheries 15: 327-351; 2014). In some fisheries, long-term investments to achieve gradual improvements in fundamental management components and supply chain sourcing policies and practices are necessary to effectively mitigate derelict fishing gear.