Lost in Time in the Galapagos Islands

By Ben Mirin, Safina Center Fellow

When father Tomas Berlanga first happened upon The Galapagos Islands in 1535, he was immediately ready to leave. His ship had been blown off course on his way from Panama to Peru, and when the ocean deposited him on these strange shores there was very little apparent food or water. Taking in the islands’ barren volcanic rock and sun beaten hills for the first time, he wrote, “I have discovered Hell on earth.”

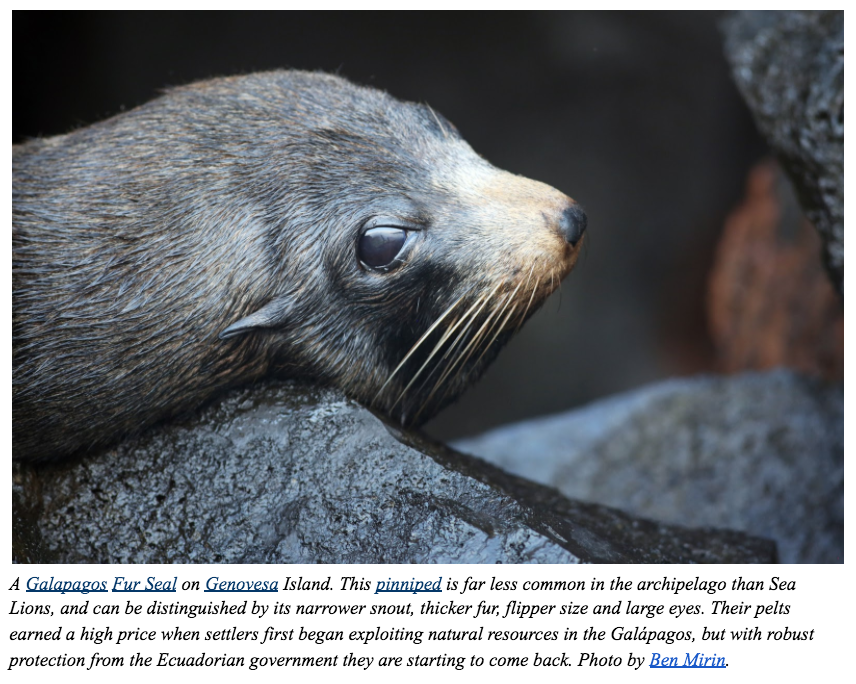

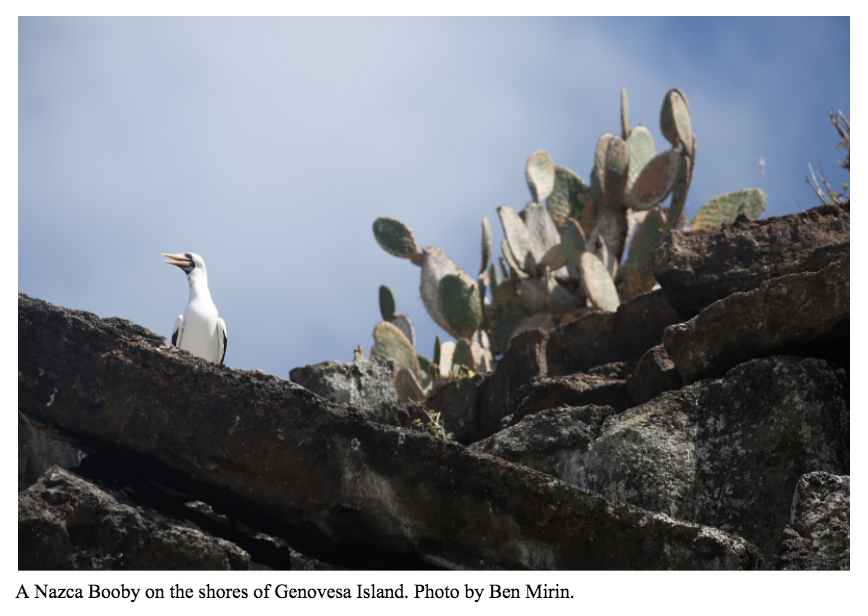

Three hundred years later, Charles Darwin was equally unimpressed, writing that “nothing is less inviting than the first appearance of these islands.” Another 183 years later, I still found it shocking. This was the land of world famous wildlife such as giant tortoises, Blue-footed Boobies, and of course the famous Darwin’s Finches whose beaks gave us our first real-time glimpse of evolution by natural selection. It was February 2018, the rainy season. But even walking in the occasional rain didn’t dampen my astonishment at how empty much of the landscape seemed to be.

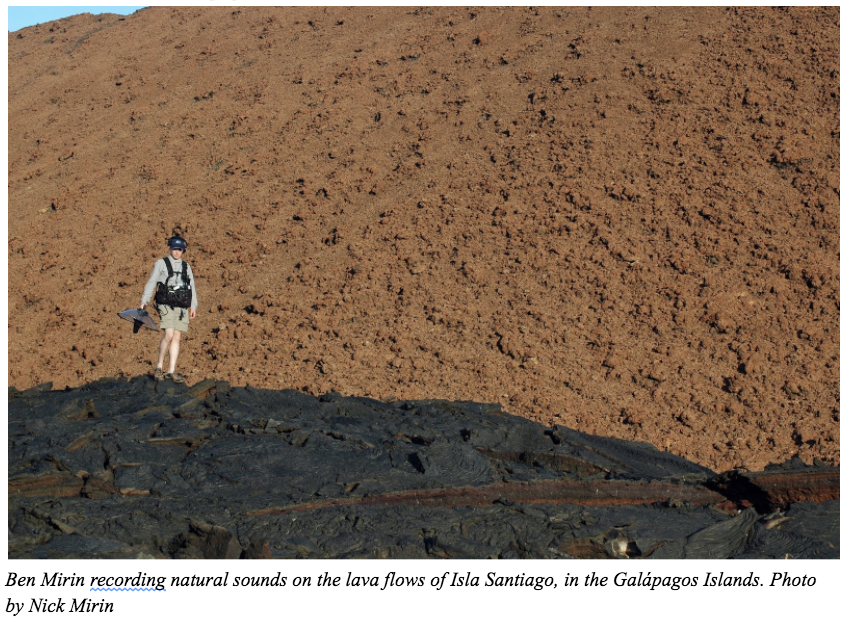

My traveling arrangements were a little more evolved than those of travelers in centuries’ past. I was to sail among seven of these islands aboard the National Geographic Islander, a cruise ship operated by Lindblad Expeditions. I was in the company of approximately forty other passengers and likely twice as many crew. Our itinerary would take us from our port in San Cristóbal to Española, Floreana, Santa Cruz and Santa Fé, Bartolomé, and Genovesa. Fortunately, I had managed to contact our expedition leaders in advance of the trip, and was given clearance to bring my sound recording equipment.

Like naturalists before me, I was blown away by how close our group could get to wildlife. But through the filter of bioacoustics, I was able to develop a deeper appreciation for the sometimes subtle varieties of species that occurred among the islands. Each landing brought opportunities to capture voices that had evolved to survive not just on this archipelago, but within a single island’s ecosystem. I found it especially challenging to distinguish the sounds of Darwin’s famous finches, which often look and sound alike, and are even known to learn each other’s songs. This often happens when one species of finch takes over another’s nest, and raises its chicks alongside those of the other.

While capturing these sounds I caught the attention of my fellow travelers and of the Lindblad staff. Julio Rodriguez, one of the staff and a former classmate of mine at Carleton College, even made a short film about my work documenting bird songs throughout our trip.

In total, our trip lasted eight days. At times it was difficult to capture pristine recordings because of the presence of other boats or visitors to the islands. But in those moments, I always remembered how those footsteps, those boats, and those planes were signs of a thriving ecotourism industry that helped sustain one of the most impressively maintained national parks I’ve ever had the pleasure to visit.