Little fish make big fish

By Paul Greenberg, Safina Center Fellow

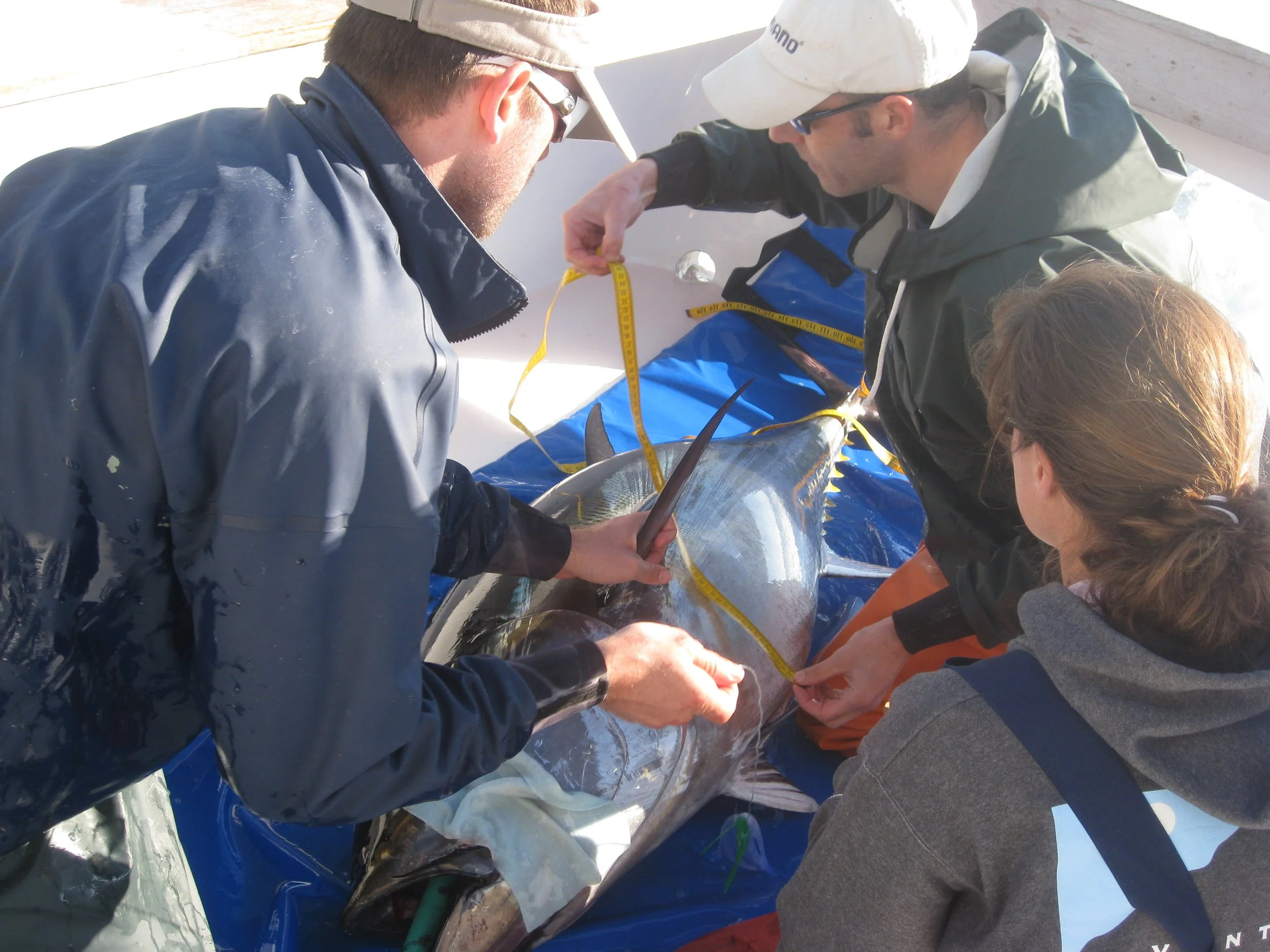

scientists measure and tag a bluefin tuna before release back into coastal US waters. © Paul Greenberg

The giants returned to New York this year.

I’m not talking about those quasi-New Yorkers who don helmets and make their home out in East Rutherford, New Jersey. I’m talking about the real native giants: Atlantic bluefin tuna which over the last month have been storming the waters of the New York Bight, sometimes finding their way onto the hooks of anglers fishing within sight of the Statue of Liberty.

The largest of the family Scombridae capable of reaching more than 1000 pounds and swimming at more than forty miles per hour, bluefin had been in steady decline in our waters for a large portion of the last fifty years. The decline is certainly due to direct over fishing of the species itself. Being a mixed stock with migrators coming from the tragically overfished Mediterranean as well as the oil-zonked Gulf of Mexico, these oversized bullet-shaped fish have had to dodge their share of bullets. Climate change too is changing migratory patterns and northern countries like the United Kingdom have also seen bursts of bluefin this year.

But having written about fisheries for the last twenty years and having observed the different things that factor into a fish’s success or failure leads me to believe that one undeniable change is driving this sudden abundance: the return of what bluefin like to eat best. That fish is an ignominious, oily, boney little animal called the Atlantic menhaden.

Atlantic menhaden. ©Paul Greenberg

Nearly every fish a fish eater likes to eat eats menhaden. Striped bass, northern bluefish, southern redfish and every major predator in between. Whales, too, make a meal of them, which is why along with the bluefin, I saw pods of humpbacks schooling within a few hundred yards of the Rockaways this summer giving a whale watching cruise to people who never had to leave the beach.

So why this sudden turn of events for the bluefin’s favorite food? Quite simply better stewardship and a willingness to stand up to industry. For years menhaden were the target of a single company called Omega Protein based out of Reedville, Virginia. For years Omega was given a Total Allowable Catch that nearly always exceeded what they company could catch. It wasn’t that the company was under fishing. It was quite simply they had fished so hard that there weren’t enough fish to fill its allocation.

But thanks to the work of activists and writers, pressure has been gradually exerted on the legislators that allowed this overallocation to persist for so many years. Beginning in the mid 2010s regulators began pushing back on the quota that for years had been assumed to be Omega Protein right. Most recently New York banned large scale purse seining of menhaden from state waters.

So is that the end of the story? Far from it. The “reduction industry” that turns all this wildlife into animal feed and dietary supplements still takes more than 20 million metric tons of fish from the global oceans every year — around a quarter of all fish caught annually. And then there are omega-3 supplements (also largely made from “reduced” little fish that predators desperately need). In spite of large clinical trials that show only modest benefit of taking the supplement, omega-3 capsules still rank among the best-selling supplements on the planet, prompting the development of an Antarctic krill industry at the bottom of the world in what by all rights should be left to the whales, seals and penguins.

Curious about all this? I was. That’s why I wrote a book called The Omega Principle that looked into the reduction industry and all its perils.

We need to keep the pressure up. We need to protect the little fish as much as try to protect the big ones. If a rising tide lifts all boats, so too does a rising population of little fish lift the chances for all the big ones.