Figure out the mockingbird

By David Rothenberg, Safina Center Fellow

Northern Mockingbird. Photo by: Kenneth Cole Schneider, Creative Commons License

Most of us have heard mockingbirds singing from the top of trees, perched on power lines, standing on the roof. They sing during the day, they sing at night. They sing boldly, extensively, virtuosically, letting loose their grand and beautiful sounds from early spring to late fall.

It’s one of the most impressive and complex bird songs in North America, but humans really understand little about how it’s put together. We call him the mockingbird because he puts this song together out of snippets of the songs of other birds, not every other singer in his vicinity, but mostly a handful of species that he pays closest attention to. Do we think he is mocking all the other singers and that’s why he got that name? Linnaeus named the bird Mimus polyglottos only by repute, he never got to see one. In French he is called the moqueur.

Well, listen carefully to said bird and you will soon realize he’s not just copying, but composing. His song follows careful rules to build on the phrases of other species, but he puts them together in a manner all his own. But strangely enough, no scientists or musicians have tried to articulate exactly what these rules are. Sure, a bird-listener can distinguish a catbird from a thrasher from a mockingbird, but we can’t always say how or why.

So this year I thought it was high time to gather a team together to figure out the mockingbird. Trapped so much at home, we all had more time than usual to listen to hours of recordings of singing birds and try to explain what is going on.

I asked around and located the world’s premier expert on the song of the mockingbird, Dave Gammon, a field biologist in North Carolina. Dave has spent years recording the songs of the mockers gracing the campus of his college, Elon University, and meticulously identifying all the species mimicked in the song, on the way discovering that quite a few mockingbird phrases are original, not copied from any bird, or any car alarm or mobile phone, for that matter. He also found out that often the birds imitate a series of sounds from one species in a row, say, the alarm call of a woodpecker then the drumming sound of the same bird. It’s as if the mockingbird is thinking, “ah, woodpecker,” and through sound conjures the other bird to life in his own sound. Like the yoiks of the Sami in Lapland, the mockingbird sings his fellow creatures into presence.

Northern Mockingbird. Photo by: Andy Morffew

Gammon has catalogued the hundreds of possible mockingbird imitations, but hasn’t thought much about musical rules that might connect these sounds together. Why should he? That’s human fare, thinking about music. Mockingbirds never called their own sounds a song or a call or anything else… Why make them into beings too much like us?

“Birds,” Charles Darwin wrote, “have a natural aesthetic sense. That is why they have evolved beautiful feathers, and beautiful songs.” Each species is a world in itself, its own musical genre, with its own sonic habits we can learn, if we want to. Only then would we know a bit more what it is like to be a mockingbird.

But how to be sure, how to be sure I am not imagining music where there is none! Science needs data, analysis, statistics that point toward proof. We needed a third approach, so I invited Tina Roeske, a computational neuroscientist in Germany who managed to illustrate five thousand nightingale songs in a single image. How might she make sense of the mockingbird? She could analyze the precise tonal and spectral quality of each phrase to make sure what we were hearing was…actually there!

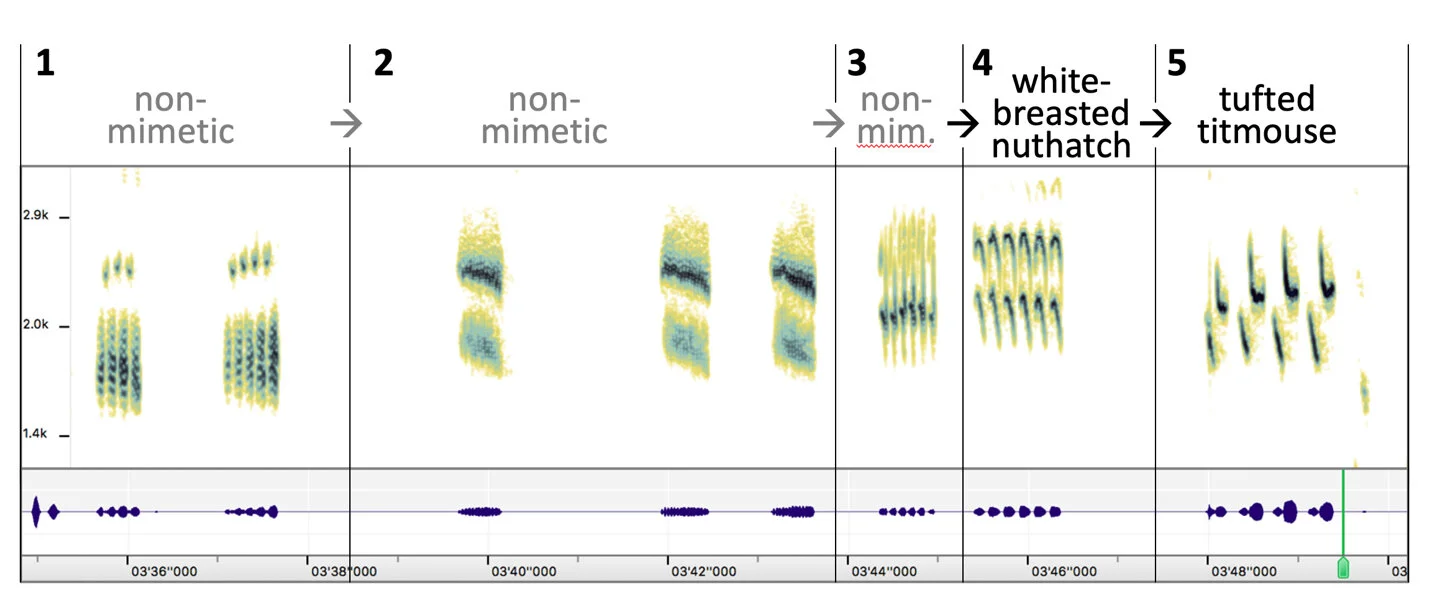

Imitations and nonimitations in a mockingbird. Image: Tina Roeske.

Watch the video below for more….

Music, ethology, sonography… three different equally human ways to make sense of nature. The musicians hears patterns, and tries to explain their structure. The ethologist or field biologist observes what animals do, and tries to take down the facts of their behavior. The statistician looks at the purely mathematical qualities of different sounds, and strives to compare them with objectivity, ending up with the kind of analysis science trusts most. We would get nowhere unless we put all these approaches together.

To make things simple we decided to pick the simplest most mockingbird-ish quality we could pinpoint in the song… the way he moves. Not in terms of dancing around on the trees, though he sometimes does that, but the way he transitions from one sound to the next. Our hypothesis was that the bird morphs one sound to the next, following a series of precise and specific rules.

At first I had eight rules, then twelve. But I remembered from my long-ago classes that in science one must simplify to find something that might be able to be proven. The more basic the better. So we got it down to four: timbre, pitch, stretch, and squeeze. Four different strategies to transform one sound to the next. Whether it be imitated, or original, this is part of the way mockingbirds move in the midst of their song.

Timbre means changing the quality of the sound, like the same music played on a clarinet, then a flute. Pitch means singing the same song higher, or lower. Stretch means taking the same phrase and sloooooowing it down. Squeeze is the opposite, taking one syllable, and then singing it just twiceasfast.

Simple, I know, but still quite hard to explain, and even harder to prove.

Dave Gammon had the bright idea of bringing in examples from human music, to show that these are basic musical concepts that even humans use often enough, though not in as stylized a way as mockingbirds do. All right Dave, I said, fair enough, but let’s make sure our human musical examples come from enough different kinds of music to suggest some universality across cultures.

So, we have Tuvan throat-singing, Beethoven, a passage from Disney’s Frozen 2, and a clip from Kendrick Lamar’s Pulitzer-prizewinning hiphop composition Damn. I could continue trying to explain the inexplicable but I think you should just watch and listen to this video to see if all this makes any hearable sense. The mockingbird examples have been pitched down and slowed down to make them more comprehensible to human ears:

All this is part of a scientific paper that we have just submitted to a special issue of the journal Frontiers in Psychology on the topic of “Songs and Signs: Interdisciplinary Perspectives on Cultural Transmission and Inheritance in Human and Nonhuman Animals.”

That might sound complicated but what it means is that a biologist and a neuroscientist and a musician got together to listen to a bird sing. And we’re still trying to crack the code. We give you some clues—now you can go out and listen to the mockingbird too. Figuring out what’s happening shouldn’t take the magic and beauty of the song away….