Climate Concerns on the Conch Coasts

By Safina Center Fellow Marlowe Starling

A queen conch peers out from under its shell off the coast of Florida. ©FWC Fish and Wildlife Research Institute

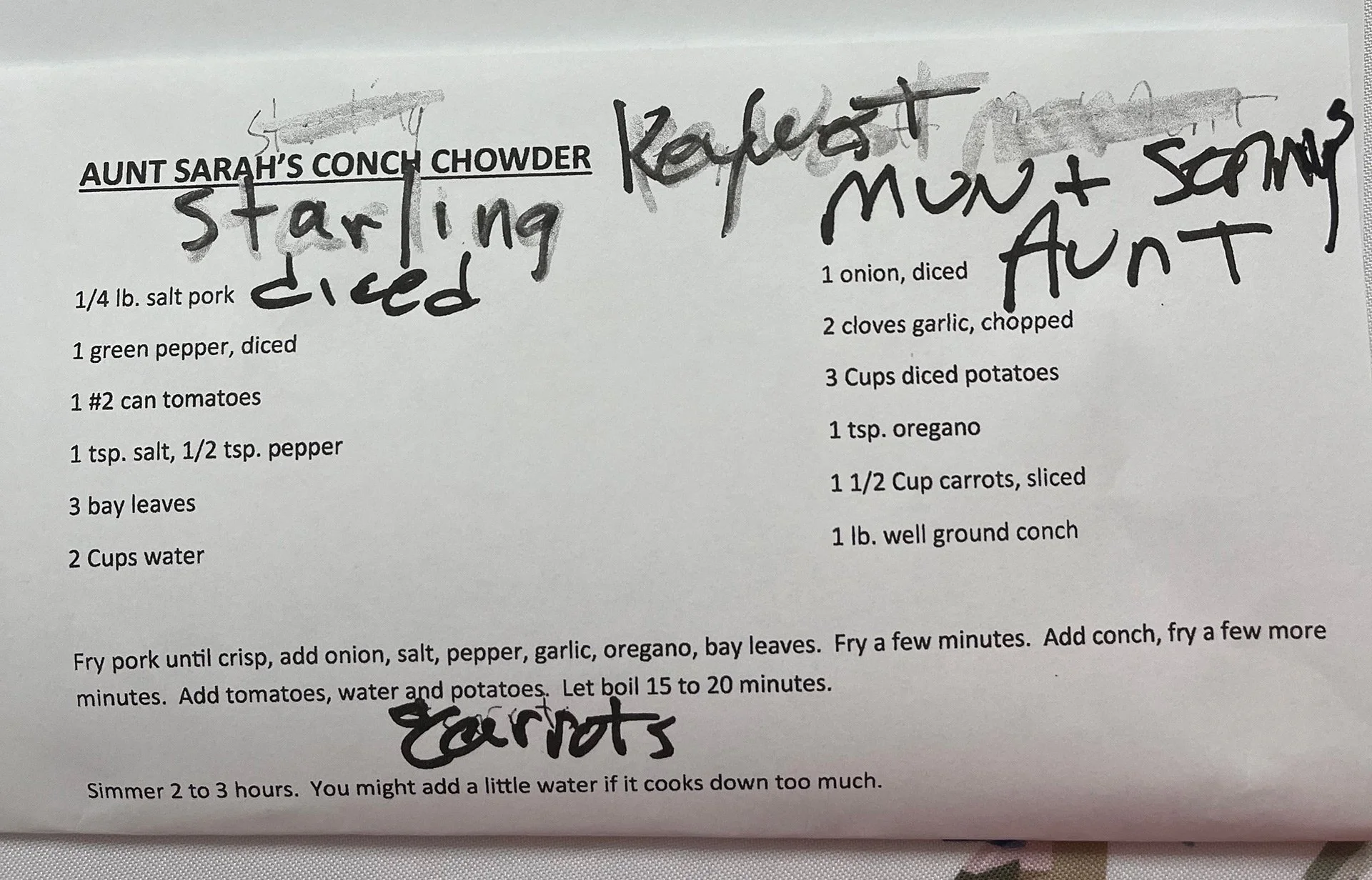

Last December, I had my first real bowl of conch chowder. Not the creamy chowder known to New England, but rather the tomato-based specialty born in the Bahamas. It was served hot out of a crock pot courtesy of a family member I was visiting for the holidays. The recipe is Aunt Sarah’s, who would have been my great-aunt (we think), from when our family still lived in Key West. The southernmost string of islands from where my family hails has long used the conch as a representative symbol. And indeed, tucked away somewhere in my parents’ garage is a royal blue Conch Republic flag—a relic of Key West’s sarcastic 1982 secession from the United States. Unsurprisingly, I love conch. (That’s konk, not konch!)

Aunt Sarah’s conch chowder recipe. ©Richard Bates

Beyond its regional significance, the queen conch, Aliger gigas, is a beautifully weird creature: its thick shell can grow up to a foot long and weigh up to five pounds with ridges and knobs along the crest that resemble knuckles, ranging in color from sandy orange to a brilliant pink. Inside, the snail-like critters are surprisingly goofy-looking. A pair of spiraled googly eyes hang on its slimy face like a sock puppet.

An adult queen conch peers out from its shell, googly eyes at the ends of two stalks. ©Daniel Neel

These royal molluscs of the Caribbean also happen to be delicious. Conch fritters, conch tacos, conch salad—they all taste characteristically Keys.

Except that it’s not. Queen conchs have been overfished so egregiously off the coast of Florida that it’s illegal to harvest them, so Florida’s conch largely comes from other countries. But even in the Caribbean, the queen conch is struggling—so much so that the U.S. listed them as a threatened species under the Endangered Species Act this past February. “The species will continue a downward trajectory, placing it at a moderate risk of extinction over the next 30 years,” a 2022 NOAA status report of the queen conch suggested. In Florida, conch populations were already struggling by the time the Keys symbolically declared themselves the “Conch Republic” in the 1980s, effectively halting conch harvests. Despite those regulations, the local population is still far from recovery.

A Conch Republic flag in Key West. ©Steven Miller

It’s an issue that spans the entire Caribbean. Scientists have attributed initial declines beginning in the 1950s to overfishing and poor management, but in more recent decades, climate change appears to be a major reason why populations are struggling to recover—even with stricter regulations. Warmer ocean temperatures are disrupting conch reproductive cycles, fueling ocean acidification that eats away at the shells, and intensifying storms that damage the seagrass beds where conchs feed.

While fisheries in the Bahamas, U.S. Virgin Islands, Puerto Rico, and elsewhere in the Caribbean are still operational for at least part of the year, the catch is nowhere near what it used to be. As conch fishery stocks dwindle, so does its cultural heritage.

On Puerto Rico’s west coast, conch holds a cultural and historical significance not unlike that of the Keys. Lorena Velez, whose father grew up near a fishing village called Puerto Real in Cabo Rojo, remembers eating any seafood her father lovingly shared with her from his natal town’s coastal bounty: octopus, dorado, and perhaps best of all, carrucho—the Puerto Rican word for conch. Empanadillas de carrucho, conch empanadas, have long been a local specialty of this part of the island. But “there are times of the year where you can’t eat it, you can't fish it,” says Velez, now an attorney at Earthjustice.

Consequently, carrucho is harder to come by. Scientists think that a break in connectivity of the barrier reef off the west coast of Puerto Rico is partly the reason why much of the region’s population has been in such steady decline. The trend prompted a decades-long effort to raise conchs in labs, with early studies dating as far back as the ’80s.

Fishing is ingrained in Puerto Rico’s history. In the days of early Spanish colonization, Puerto Real was the most bustling port on the island and the center of its fishing industry. But in more recent decades, many of Puerto Rico’s fishing communities have been squeezed out by tourism and gentrification. Puerto Real now faces high poverty rates and has been largely ignored in post-disaster recovery efforts. Velez and a network of other attorneys and activists are researching a larger project to study how women are disproportionately impacted by disaster recovery efforts and climate change policies in Puerto Rico. And it’s not just here; in Barbados, developers are similarly pushing out local fish markets without consulting with fishers or offering alternative locations.

A 1942 photo of Puerto Real in Cabo Rojo, Puerto Rico, an “extremely poor little fishing village,” the photographer wrote. ©Jack Delano, Provided by Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, Farm Security Administration/Office of War Information Black-and-White Negatives

As Velez grew older, she noticed an interesting trend: It was always women behind sales counters selling the catch brought in from offshore. And the few women who joined fishing crews out at sea were often outcast by the men.

“When you go to a lot of the places where you can buy fish, you find a lot of women that are the center of the business,” Velez said. “That's part of that fishing economy and practice. Because you can fish, but what are you going to do with it later?”

In some cases, fisherwomen are discouraged from fishing out of a paternal social construct; in others cases, fishermen insist it’s a privacy issue to be on a boat all day with no proper bathrooms, Velez learned through interviews for her research.

The trend isn’t unique to Puerto Rico. Elsewhere in the world, women are similarly shut out from decision-making in fisheries management despite being an integral part of inshore harvests (for example, molluscs, shellfish, and baitfish) and the backbone of fish market business operations.

In Barbados, a community working group is using participatory theater to help promote social and climate justice for fisherfolk—specifically for women. Through poetry, videos, and other art forms, the group of fisherwomen, called Voices from the Shore Theatre Collective, has helped spread awareness of the layered challenges women face in the fishing industry, from social inequities and crimes at sea to the biodiversity crisis and mounting climate concerns. For example, the region’s steep influx in sargassum, an overabundant floating macroalgae, is impeding flying fish catch for small-scale fishers.

“Not only is fishing something that is being impacted by climate change, but women who are already disproportionately impacted by climate change” have added challenges, Velez said, such as poverty and government neglect.

As queen conchs fight for survival in the Caribbean, so too do the queens of its fisheries.