Changing climate means changing times for fish and shellfish in New England and beyond

By Erica Cirino, Safina Center Launchpad Fellow

Dr. Jon Hare and his colleagues at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) have just published the results of two years’ work: their first assessment of fish and shellfish species living along the New England coast.

What Hare and his colleagues have found: climate change is expected to decimate the populations and shift the range of more than half of the most commonly consumed New England fish and shellfish. About 30 percent of the species will likely be unaffected, and 17 percent are projected to benefit from climate change.

Increasing ocean temperatures, changes in ocean salinity and circulation, sea level rise and ocean acidification are some of the biggest threats to fish and shellfish. NOAA scientists project how ocean species’ numbers and ranges may change by using current trends in these changes and a database of information on conditions under which each species thrives.

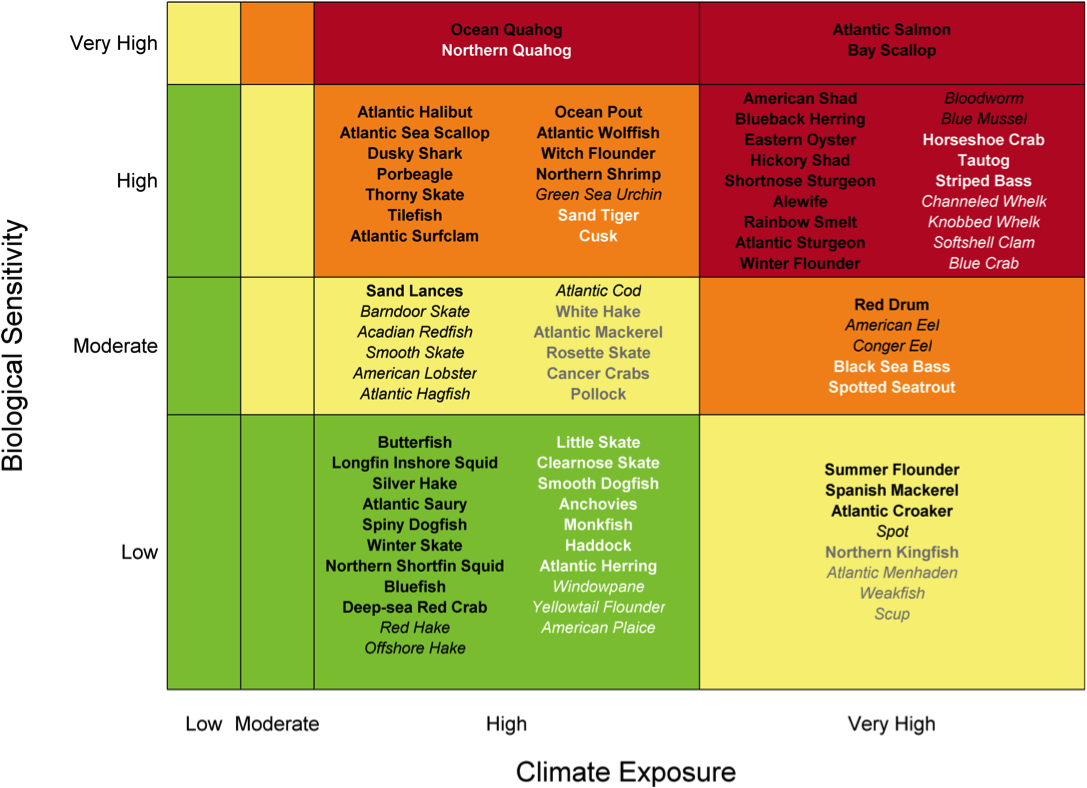

The NOAA scientists have organized their findings in a color-coded chart that neatly summarizes species’ vulnerability. The idea is to make it simple for those overseeing the nation’s fisheries to understand which species are most likely to be harmed by climate change, and which may actually benefit from a rise in global atmospheric temperatures. This can help guide the development of conservation programs and fishing policy decisions, says Hare.

Hare, et al. 2016.

Right now the people tasked with overseeing fish populations should know it’s the species living on or near the seafloor—such as scallops, clams, flounder and lobsters—and those that migrate between fresh and salt water—like Atlantic salmon and sturgeon—that are most likely to be harmed by climate change. Species living near the water’s surface, such as herring and mackerel, are least vulnerable. Other species, like Atlantic croaker and black sea bass, may respond positively to a warming climate, increasing in population and distribution.

“This kind of assessment will be a key component for making management plans to ensure U.S. fisheries remain sustainable and resilient in the face of future climate change,” says Dr. Christopher Gobler, marine biologist and a professor at the School of Marine and Atmospheric Sciences at Stony Brook University. “When setting future quotas for fisheries, it will be important to err on the conservative side for species most vulnerable to climate change processes.”

The effects of climate change on fish and shellfish go much further than just conserving species: New England’s fisheries are worth nearly $200 billion and provide 1.7 million jobs, NOAA reports. New England and other coastal economies suffer without healthy fisheries.

Climate change shows no signs of stopping: Humans’ steady stream of greenhouse gases into the atmosphere has caused 15 of the 16 warmest years on record to occur since 2001. Human-created emissions have also caused atmospheric levels of carbon dioxide, a major greenhouse gas, to exceed “the 400 parts per million threshold this winter for the last time,” says Gobler. “We will never be below that number again in our lifetime.”

With the Northeast assessment now complete, NOAA scientists are now studying how species in the waters off Alaska and the Pacific Northwest will fare. Eventually, Hare says, his group will assess fish species in the waters off the U.S.’s Southwest and Southeast coasts, and the Pacific Islands.

If you eat seafood, you can do your part by choosing to consume fish and shellfish species that are least vulnerable to climate change. Use the Monterey Bay Aquarium’s Seafood Watch to help you make more sustainable seafood choices.