Black Faces in Blue Spaces

By Jacqueline L. Scott, Safina Center Senior Fellow

Lake Ontario figures a lot in my imagination, simply because I spend so much time beside it, usually daydreaming. Being down by the lake is calming. I bicycled about 500 miles, or 1,000 kilometres, around it last summer for the adventure, and to search for the Black history hidden in the countryside and small towns.

The waters of Lake Ontario vary in colour from cobalt, indigo to aquamarine. This blue-space – bodies of water in the form of a sea, lake, river, pond or reservoir – is natural. Others are man-made. Visiting blue-spaces makes us feel better, and it reduces stress and anxiety. The sound of water is relaxing, even when it is the roar of Niagara Falls. Connecting to nature is easier in blue-spaces: wade in a pond to catch tadpoles and crayfish, stand on the riverbank to fish, walk around the lakeshore for birdwatching. Living close to a blue-space is good for us mentally and physically. And we are more likely to notice and care about conserving the nature around it.

A summer day by the beach in Toronto. ©Jacqueline L. Scott

There are many blue-spaces in Toronto, from Lake Ontario to the rivers, and the streams in the city’s ravines. Race shapes who has access to these. Houses close to the lake or backing onto the ravines are more expensive. And the people living in these areas are more likely to be white. Black people tend to live in apartments which are further away from blue-spaces.

People living next to a body of water tend to go there frequently. For instance, those near the beach are more likely to visit it, not just in the summer but during the rest of the year, winter included. A summer swim or an autumn walk by the beach refreshes the spirit and exercises the body. These positive effects are greater for poor people. In Toronto, the poor tend to be Black, Indigenous, and people of colour. It was not so long ago that beaches and mineral spring baths were segregated in USA and Canada, excluding Black people from the benefits of being in nature in these blues-spaces.

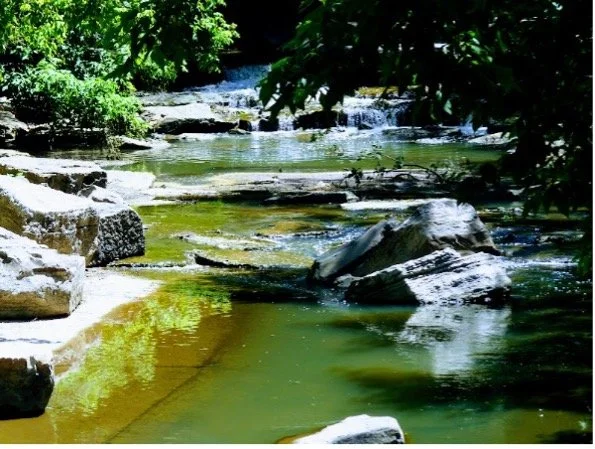

Blue-spaces near where Black people live may have other barriers. For example, a stream in a ravine is inaccessible if people don’t feel safe being in the woods. The lack of maps and trail makers in Toronto’s ravines hinders exploring them. In addition, poor people are more likely to live near blue-spaces that are degraded. The streams tend to be channeled into ugly concrete sleeves, or stink of raw sewage sluggishly flowing through them. These degraded habitats are poor in wildlife such as fish, birds and amphibians. One is not tempted to splash into these waters to cool the feet in the summer, or to encourage children to enter them to look for bugs and frogs.

A stream in a ravine in a rich area. ©Jacqueline L. Scott

‘What happens to the water happens to the people.’ This was our rallying chant at a Toronto demonstration in support of the Indigenous community of Grassy Narrows, Ontario. Toxic mercury waste, from industrial paper production, was dumped into their river. The mercury poisoned the fish. The people ate the fish which was a key part of their diet. The fish poisoned the people. Some fifty years later, the community is still struggling with the fallout of mercury poisoning.

Humans are wired to prefer landscapes with views of water. This is one reason hotel rooms, and berths on cruise ships, with a sea view costs more. It is the same for apartments and houses with views of blue-spaces. Race shapes who gets the pretty views of clean blue-spaces, and who gets the ugly views of polluted waters.

On my bike ride around Lake Ontario, I passed many rivers and streams emptying into the lake. Sometimes I knew that I was close to them simply from the stench of sewage or acrid chemicals bruising my nose. The lake is huge, but it is not big enough to cope with the levels of pollution. It can’t sink or wash away these human-made problems. Polluted blue-spaces are bad for nature and bad for humans too.

Still, there is good news. The Atlantic salmon have returned to Lake Ontario and other blue-spaces. Once abundant, and food for Indigenous communities, the fish became locally extinct due to the negative impact of European colonialism and settlement. Cleaning up the blue-spaces and conservation restoration brought the fish back. We need more conservation success stories like these.

On the shores of a small town, on my long bicycling around Lake Ontario, I saw a Black man teaching his small son and daughter how to fish. The Black faces were enjoying a blue-sky day in a clean blue-space. We need more stories like these, too.