Biomedical Innovation Makes Horseshoe Crab Blood Obsolete

Guest blog by Abigail Costigan

Many males cluster around female horse crabs during spawning bonanza in the Peconic Estuary. ©Abigail Costigan

Horseshoe crabs once seemed as abundant as bacteria—and almost as incendiary. From colonial times, they were shoveled into massive heaps on the beach, fed to pigs, and ground into fertilizer for crops. An estimated one million horseshoe crabs were killed this way, their tails taken to town hall and their bodies thrown above the high tide line to rot, per year. Massachusetts towns put bounties on them, paying three cents per tail to keep these nuisance predators from eating valuable shellfish.

Today, they are used to save human lives. In a massive breakthrough from almost seventy years ago, a medical researcher discovered horseshoe crab blood could be used to detect bacterial infections in people.

Horseshoe crabs piled on the shore of the Delaware Bay, destined to become fertilizer. Photo courtesy of Delaware Public Archives.

Fred Bang arrived at Woods Hole, Massachusetts in 1952 with his wife Betsy. He was a medical researcher; she was a scientific illustrator. In 1956, Fred and his student Jack Levin at the Marine Biological Laboratory discovered horseshoe crab blood quickly clots around gram negative bacteria, which can cause infection and/or death. For an animal with an open circulatory system living in the bacterial soup of the ocean, this is an advantageous adaptation. It allows them to quickly and effectively surround and stop invading bacteria from spreading.

As an illustrator, Fred’s wife, Betsy Bang, paid close attention to detail. By the time her husband’s research into horseshoe crabs began to bear fruit, her careful dissections had already led to pioneering biological findings, like the first-ever description of a bird’s olfactory system, which lent evidence to the fact that birds have a sense of smell. Her finding did not just confirm a widespread belief, but offered evidence contrary to the broadly accepted assumption that birds had lost their sense of smell to improve their eyesight—a story pushed by famous (and famously problematic) ornithologist John James Audubon. By paying attention to the internal workings of birds rather than the established findings of men, she changed the dominant narrative.

The fossil record proves horseshoe crabs are anatomically efficient. Their body design has barely changed over the past 450 million years.

Horseshoe crab fossil from the Jurassic period. ©Abigail Costigan.

But they are not indestructible. Horseshoe crabs take about 10 years to reach maturity. Of the four extant species, only the American horseshoe crab is not considered endangered or too data deficient to tell (all three species living in Asia are). Further, horseshoe crabs are a key link between the marine food web and coastal ecosystems. Their spawning conveniently occurs on beaches, injecting necessary and high quality nutrients in a range of shorebirds and other coastal animals. For example, the bird known as the Red Knot relies on consuming horseshoe crabs’ fat-laden eggs as they migrate from the tip of South America to the Arctic. Without an abundance of eggs available to them, they face much lower odds of fledging their chicks.

Humans, too, are at war with gram negative bacteria. They induce fever, anaphylactic shock, and cause all sorts of diseases, from meningitis to the bubonic plague. Bang’s discovery resulted in horseshoe crab blood—or more specifically, the binding compound present within it called Limulus Amebocyte Lysate (LAL)—being widely used in the medical industry to test the cleanliness of medications and devices. Now, instead of being toted off beaches by the wheelbarrow load to be used as fertilizer, biomedical companies bleed the crabs in labs, taking 30% of their blood at a time. They then transport them back to the bays and release them back into the water. Most of them survive this process, but an estimated 15% do not.

Bang’s 50’s-era LAL discovery was revolutionary. But now, it’s 2024. The world has changed. We don’t watch Howdy Doody anymore and the human population has increased by six billion. You can’t smoke inside, but you can marry someone of the same gender or different race. We are worried about COVID, not Polio. Non-critically maintaining the status quo of LAL extraction is outdated, and frankly, just plain lazy.

Horseshoe crabs in the Long Island Sound. The male horseshoe crab uses specialized front legs to grasp onto the female in order to reach peak spawning position when she digs a hole and lays her eggs. ©Abigail Costigan.

We live in a time of widespread ecological collapse and fast paced changes brought on by climate change. Maybe we shouldn’t rely on a single arthropod found in a single country to test all our drugs on anymore.

In July, the US Pharmacopeia’s Microbiology Expert Committee answered that call by voting to adopt Chapter 86: Bacterial Endotoxins Test Using Recombinant Reagents. This creates a path forward for the biomedical industry’s use of a synthetic alternative to horseshoe crab blood in bacterial endotoxin testing, which has been approved in Europe since 2019. It’s a huge win for environmental organizations like the Horseshoe Crab Recovery Coalition, and for activists that have pushed for tighter horseshoe crab regulations.

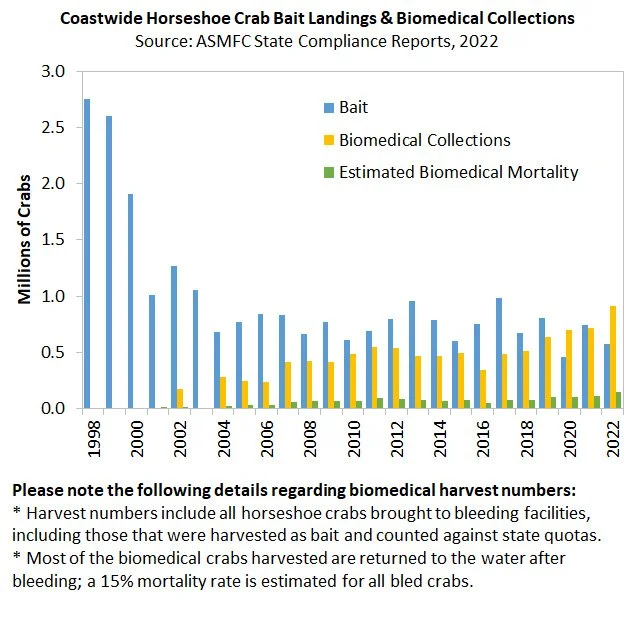

Still, threats to horseshoe crabs abound. Shoreline development and rising sea levels make it harder for them to find suitable spawning habitat. Almost a million horseshoe crabs are taken for bait on the East Coast of the US, according to the Atlantic States Marine Fisheries Council, which is tasked with managing the population.

ASMFC Bait and Biomedical Horseshoe Crab Landings for the entire Atlantic coast. Source: Atlantic States Marine Fisheries Commission

What we need now is deeper investment in the understanding of horseshoe crabs rooted in how they interact with and in their environments—not continually extracting their blood for medical applications that can today be achieved through synthetic means. In other words, it may be time to take a page out of Betsy’s book instead of continuing to read the old one written by her husband.