As Waters Warm, the Wildlife Will Wander

By Safina Center Fellow Marlowe Starling

Climate change is shifting coastal wildlife communities north. Is it time we normalize it?

Striped sea robins are becoming more abundant in Narragansett Bay as water temperatures increase. They also prey on young flounder, which hurts the commercial flounder fishing industry. There isn’t a big market for striped sea robins. ©Gretchen Ertl/Metcalf Institute, University of Rhode Island

Fewer than thirty steps onto the beach at Jacob Riis Park in Queens, I came across an unexpected sight: a dead shark half-buried in the sand. Three children were huddled around the carcass, a bite seemingly taken out of its side. At barely three feet from nose to tail, it looked like a smooth dogfish (Mustelus canis), a small shark that’s common along much of the Atlantic coast. The kids said it had washed ashore dead, so now they were giving it a dignified funeral. Odd as it was, we said goodbye and parted ways.

A smooth dogfish carcass found on the beach at Jacob Riis Park in Queens, NY. ©Marlowe Starling

About four hours later, a large crowd formed around something writhing on the shore. Even from far away, I could see from its glistening grey skin that it was another shark, almost identical to the first one.

The crowd grew larger, staring at the shark as it thrashed around, and I heard the life guards telling people to leave it there because it could be sick. I also heard them telling people that it was a sand shark (a species that doesn’t exist) and that they “aren’t supposed to be here” this time of year. That’s when I raised a high eyebrow.

Ocean temperatures are higher than they’ve ever been. Sea surface temperatures made records in 2023 and are continuing to get hotter, leading to a series of consequences which have killed off coral reefs at unprecedented rates. It has also pushed some species north, especially those that need cooler temperatures. Leaving sharks to die onshore because of arbitrary range limits—especially for a species that doesn’t voluntarily beach itself—seemed like weak reasoning. It’s not uncommon for small sharks to accidentally forage too close to shore and get sucked into a strong current, pushing them into the surf.

Here’s the truth: Virtually nothing is “supposed” to be here this time of year. Climate change has shifted baselines north for the foreseeable future. Perhaps no better evidence of this exists than in my home state, Florida. Invasive reptiles like green iguana (Iguana iguana), Argentine black-and-white tegu (Salvator merianae), Burmese pythons (Python bivittatus), and brown anoles (Anolis sagrei) have dominated the state’s swamps and urban environments alike. Roseate spoonbills (Platalea ajaja) have started to move out of Florida Bay and up the East Coast. And mangroves are slowly shifting northward, too, in stride with neo-tropical environments.

The trend isn’t limited to land. In the Gulf of Mexico, a recreational sport fish called the common snook (Centropomus undecimalis), though less commonly known among anglers outside of South Florida, has made its way up to Cedar Key and the panhandle—a notable phenomenon to fisheries scientists because of the snook’s sensitivity to cold temperatures. They predict the snook can survive there because the waters are now warm enough for them to persist.

But across the U.S., other fisheries are changing because of a warming world too.

New England’s new ecology

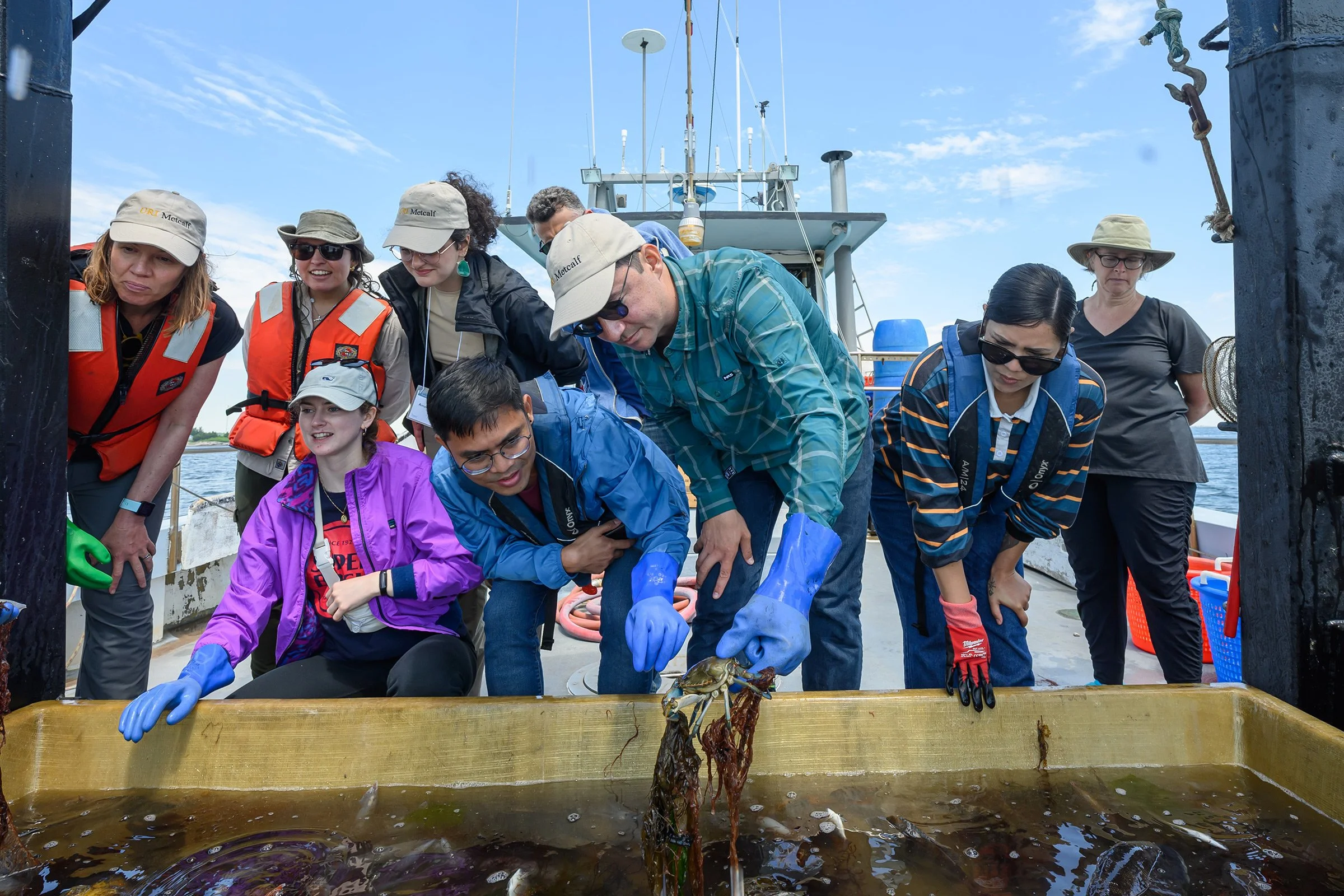

Affectionately self-nicknamed “Metcrabs,” the 2024 cohort of Metcalf Institute Fellows, examine the diversity of fish species brought onboard the Cap’N Bert from a demonstration fish trawl in Narrangansett Bay. ©Gretchen Ertl/Metcalf Institute, University of Rhode Island

In early June, I joined a crew from the University of Rhode Island’s oceanography department on the Cap’N Bert, a research vessel for taking trawl surveys. As a fellow with the Metcalf Institute, I was there to learn about the ways climate change and water quality intersect, and on that day, we were focused on how tiny plankton form the foundation of a biodiverse Narragansett Bay.

But I had a slightly tangential interest: Are there any species that historically lived here and no longer do? And conversely, are there “neo-native” species, as the Florida scientists dubbed the common snook in the northern Gulf of Mexico?

Captain Stephen Barber had answers. Within the past few years, winter flounder (Pseudopleuronectes americanus)—a cold-adapted species—have virtually disappeared from the bay, he told us. So have lobster, which are marching northward at a pace that’s outrunning commercial fishermen. Meanwhile, warm-water species like black drum (Pogonias cromis) have moved into an ecosystem that now looks more like Chesapeake Bay, Barber and his graduate students told me, adding that Narragansett Bay has warmed about 2 degrees Celsius (roughly 35 degrees Fahrenheit) since 1965.

Riley Secor, a doctorate student in marine science at University of Rhode Island, displays a summer flounder aboard the Cap’N Bert, a species that has become more abundant as the water temperatures have increased over time. ©Gretchen Ertl/Metcalf Institute, University of Rhode Island

Using decades of fish trawl survey data, the University of Rhode Island’s Graduate School of Oceanography team published a study analyzing how these shifts in local biodiversity may be related to the trend of warming water. As the water warms, it increases the metabolic demand of cold-adapted species, meaning they don’t grow as quickly. That makes them easier prey for warm-adapted species.

“If climate change means that winter flounder can’t be rebuilt, fisheries managers may have to shoot for more modest goals that reflect the diminished capacity of warmer oceans,” wrote Ben Goldfarb in a 2022 Hakai Magazine article about Rhode Island’s disappeared fishery.

Although climate change is a major culprit, there’s another factor rooted in basic ecology. University of Rhode Island researchers have documented a 49% decrease in phytoplankton biomass— the base of the food chain for all of the bay’s organisms—over the past half-century, reported local environmental newsroom ecoRI. Less phytoplankton ultimately means less of everything.

Marlowe Starling and other Metcalf fellows peer inside microscopes to see the phytoplankton they collected on the Cap’N Bert earlier in the day. ©Gretchen Ertl/Metcalf Institute, University of Rhode Island

Stranger things have come with the warmer tides too, like a lone manatee found wandering around the bay in 2023 that was later found dead offshore.

In the case of the common snook or winter flounder—mesopredators that sit comfortably in the middle of the food chain, keeping smaller grub in check while feeding the larger predators—their disappearance from historic sites and introduction into new ones forces changes in local marine ecosystems. But it also affects the people who earn a living from the coast, in ways both good and bad.

For commercial fishermen, especially those who run multigenerational businesses, those changes can take a toll. The declining lobster fishery in Rhode Island has left fisherfolk to swap $10-apiece lobster for $1-apiece crabs, making earnings slim enough to encourage overfishing. Plus, switching from one commercial species to another is no simple task. It requires buying new gear, learning new regulations, and vying to earn a living in an increasingly crowded and competitive market. And sometimes, there aren’t obvious fish species to target in lieu of one that has disappeared. Striped sea robin (Prionotus evolans), a local species that has become more abundant as waters have warmed, are partly to blame for winter flounders’ decline. But there isn’t much of a demand for striped sea robin commercially.

Marlowe Starling posing with a striped sea robin onboard the Cap’N Bert. ©Gretchen Ertl/Metcalf Institute, University of Rhode Island

These changes can also have the opposite effect. Captain Denny Voyles, a recreational fishing guide in Cedar Key, Florida, told me back in 2020 that snook’s arrival was exciting. Although the snook are potentially competing with red drum (Sciaenops ocellatus) for food in the shallow bay where Voyles takes his clients fishing in the winter, it also presents a new opportunity for them to learn about a fish few people know about. For Voyles, it’s an opportunity to share his love for the local environment with his clients, many of whom visit from the Northeast and Midwest.

Fisheries managers get creative

Capt. Stephen Barber prepares the net for the research team’s trawl survey. ©Gretchen Ertl/Metcalf Institute, University of Rhode Island

Meanwhile, in Maryland’s rivers, state wildlife agencies are encouraging a new fishery to help manage a booming population of invasive blue catfish (Ictalurus furcatus). It’s an approach to invasive species management that benefits the ecosystem while providing commercial fisherfolk with a new source of income.

Blue catfish are generalists, explained biologists with the Maryland Department of Natural Resources, depleting much of the native prey that are economically important, like blue crab, menhaden and American eel — similar to how Burmese pythons have overrun the Everglades. They also reproduce extremely well, laying about 3,500 eggs per pound of body weight; females can weigh up 20 to 30 pounds. Wildlife managers were forced to realize that the fish weren’t going away.

Their saving grace? Blue catfish have two traits that make them great candidates for both a recreational and commercial fishery: They’re fun for anglers to fight at the end of a line, and they’re good eating.

Unlike in Rhode Island, where creating new fisheries opportunities is difficult, Maryland’s commercial landings of blue catfish have increased 500% in just ten years. The growth signals the expansion of blue catfish in the state’s waters, but it also signals the success of the new fishery—one that both recreational and commercial fishermen are excited about, natural resource managers told me. And as some fishermen switch their focus catch to blue catfish, that also takes pressure off existing fisheries, like striped bass, for example. There’s even a new commercial fishing license in Maryland specifically for running trotlines to catch blue catfish, a fishing method that uses one long line with several shorter baited lines to hook fish.

So, what if state and federal agencies started treating newcomer wildlife as normal versus nuisance? And what if we shifted our mindsets the same way scientists are being forced to shift their baselines due to a rapidly warming world?

Starling and other “Metcrabs” pose for a photo with a tank full of fish harvested during a trawl survey in Narragansett Bay. ©Gretchen Ertl/Metcalf Institute, University of Rhode Island

As sea levels rise and our homes become too hot, we will inevitably migrate elsewhere. We should expect the same of our coastal neighbors.