A hands-on plastic science experiment in the age of online learning

By Erica Cirino, Safina Center Launchpad Fellow

A local (Long Island) beach. Photo: Erica Cirino

The author, masked up. Photo: Erica Cirino

I cannot imagine what it’s like to be a high-school student today, I think, as I log into my latest Zoom lecture. Like all other public speakers, my talks have gone online in 2020. Instead of looking out into the depths of a classroom or auditorium, I am peering into my computer screen. The boxes showing each students’ video stream are windows into 10 different homes. The youthful faces looking back at me are unobscured by the masks that have become a permanent fixture of our faces in public.

I’m giving a lecture to teens about plastic pollution and my work as a photojournalist and researcher covering the story around the world. My host is Avalon Park and Preserve’s Nature Initiative, an education program for young people based on Long Island. The students look weary, a few with dark circles under their eyes.

How am I going to get them excited to learn anything on this mild fall evening, an evening where normally they might be running around outside playing with friends? Do they really need more time staring at a screen when so much of their school curriculum and social life has gone online?

I open up our call asking how everyone’s doing.

“It’s been really hard,” one student offers. “I’m tired of screens.”

“I actually miss school,” says another, who had not had any in-person learning all year. “I miss my friends.”

I tell the students I hear them, and reassure them that tonight won’t be the typical Zoom call. The students perk up. I remind them to take out the small baggies I’ve prepared for them, which they’ve each picked up at Avalon’s Preserve. In each bag was a science experiment.

Science experiment in a bag! Photo: Erica Cirino

This was an idea conceived when brainstorming how to make online learning less…well, online. In pre-Covid days, I’d take students to a beach. There I could show them washed-up plastic items and particles they can feel and hold. I could tell them how the plastic may have been littered on the beach by careless people, or it may have blown, rolled, flew or washed onto the shore from somewhere else.

Scouring a Long Island beach for plastic items and microplastic with third graders, in pre-Covid times. Photo: Erica Cirino

Photo: Erica Cirino

My whole goal is to show the students how the plastic things we use every day, especially those things classified as “single-use plastic”—namely, packaging we use for mere moments before throwing it away—break up into microscopic particles that pose risks to human and ecological health. These little particles are called microplastic, and they completely permeate our world. They are in our indoor and outdoor air, freshwater, oceans, food and soil. They are inside wild animals and they are inside of us humans too. Research suggests the chemicals in these plastic bits are making all of us sicker than we should be. Our hormones no longer function normally, cancer rates have skyrocketed, and we now suffer an increased rate of all sorts of other issues—mental health, autoimmune, reproductive and otherwise—that could be linked to the chemicals in plastic.

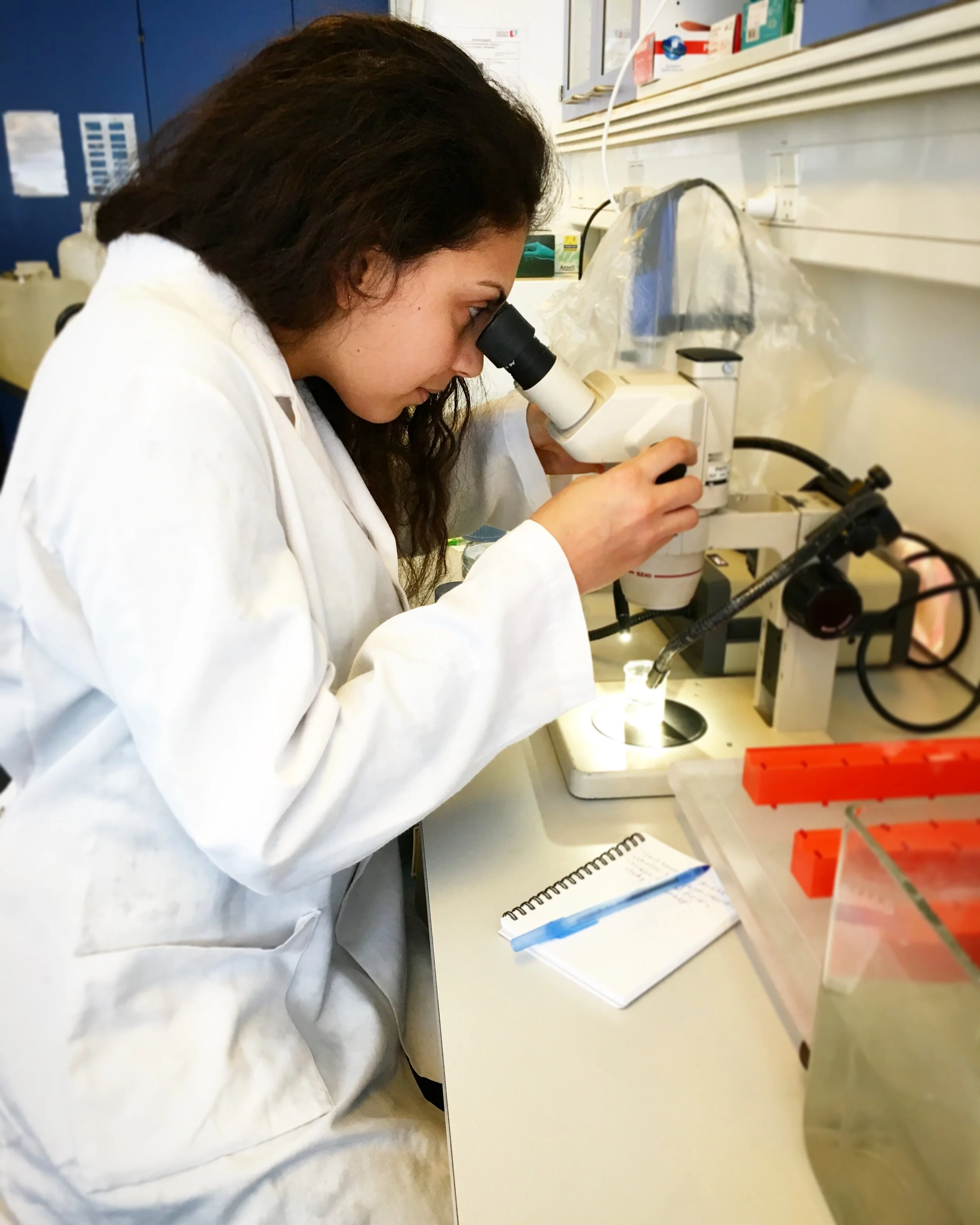

I tell the students scientists are constantly trying to better understand the scope and implications of this issue that affects every being on this planet. I show them photos of plastic I’ve taken in the middle of the Pacific Ocean, in Iceland, in Copenhagen, in Thailand, in Los Angeles, in Myanmar, in the Marquesas. I tell them how I studied plastic—counting the pieces, using my eyes and special machines that can determine the chemical makeup of a particle in mere seconds by bombarding it with beams of infrared light.

Plastic pollution on Nai Yang Beach Thailand. Photo: Erica Cirino

A handful of plastic from the waters off Kamilo Beach on Hawaii. Photo: Erica Cirino

The author in a lab in Denmark, studying microplastic up close. Photo courtesy: Erica Cirino

Then I tell them they can be plastic scientists too. The students look skeptical. The baggies, I remind them. Take them out!

The baggies are filled with sand collected from a local beach. There’s microplastic mixed in the sand. I give them clues for how to trace each tiny piece of fiber, fragment, film, foam and pellets back to the item from which it came. This, in an attempt to show the path of plastic into our natural environment, and the implications of it getting there. The students will work as plastic detectives, using their eyes and sense of touch. A fiber might have come from a rope; a piece of film from a bag; a fragment from a plastic container; a crumble of foam from a cup; a raw plastic pellet from a spilled container ship.

Photo: Erica Cirino

Inside the bags! Photo: Erica Cirino

All but one of the students look extremely excited to rip open their baggies (which are paper, not plastic). She looks at me with big eyes. Her voice trembles. “So,” she says bravely. “What you’re saying is that the plastic all around us, the plastic that fills our homes and our lives and that we eat off of and drink out of and get our food in, and our phones, and our clothes…all of this is breaking off into little pieces and it can make us and animals sick?”

I pause. What do you say to a question like this? How do you tell a child that the world that is their home has been rendered nearly inhospitable, by our own human hands?

“Yes,” I say. I decide to tell her the truth. “You’re right, and the situation is not good. But we can change things for the better. People like you can make a difference.”

I conclude my lesson and encourage the other students to leave the Zoom call. “Go and be a scientist for a night, it might change your life," I tell the students. “There is much to do, and only so much can be achieved through a screen. We need you to get out there.”

The students smile eagerly and I know they understand.